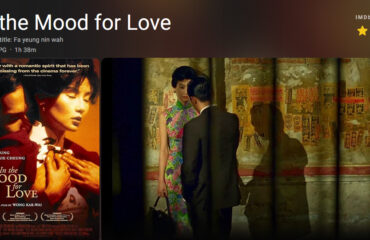

The cheongsam, or qipao, is an icon of Chinese culture, instantly recognizable for its elegant, form-fitting silhouette, high collar, and delicate craftsmanship. In the modern global imagination, it often evokes images of demure femininity, nostalgic glamour as seen in films like “In the Mood for Love,” or a formal garment reserved for special occasions. However, to confine the cheongsam to these narrow definitions is to overlook its radical and revolutionary history. Far from being a timeless, traditional costume, the modern cheongsam was born in an era of immense social and political upheaval in early 20th-century China. It emerged not as a symbol of restriction, but as a powerful and visible statement of female emancipation, modernity, and a burgeoning national identity. Its evolution from a loose-fitting robe to a tailored dress that celebrated the female form is a story inextricably woven with the struggles and triumphs of Chinese women seeking to break free from the shackles of feudal patriarchy.

1. From Imperial Robes to Republican Revolution

To understand the cheongsam’s liberating power, one must first understand the world it replaced. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), women’s clothing was designed to conceal and constrain. Han Chinese women wore a two-piece outfit of a loose jacket and trousers or a skirt, while Manchu women wore a long, wide, A-line robe called the changpao. Both styles were characterized by their voluminous cut, which obscured the body’s natural shape, reflecting the Confucian ideal of female modesty and subordination. Women, particularly those of the upper classes, were largely confined to the domestic sphere, their identities defined by their relationships to men. The painful practice of foot-binding further symbolized this physical and social restriction.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and the establishment of the Republic of China heralded a new era. Influenced by the May Fourth Movement and the New Culture Movement, intellectuals called for the rejection of old Confucian traditions in favor of “Mr. Science” and “Mr. Democracy.” Central to this was the call for women’s liberation, including access to education, an end to arranged marriages, and the freedom to participate in public life. It was in this fervent atmosphere that a new style of dress began to emerge. Young, educated women, particularly students, began to adopt a modified version of the changpao, straightening its silhouette and simplifying its design. By wearing a garment originally associated with Manchu men and adapting it for themselves, these women were making a profound statement. They were symbolically shedding the old, layered clothing of the past and embracing a simpler, more unified, and androgynous look that rejected traditional gender-based dress codes. This early, loose-fitting cheongsam was the uniform of the new, intellectual woman.

2. The “Modern Girl” and the Shanghai Silhouette

The evolution of the cheongsam accelerated dramatically in the cosmopolitan metropolis of Shanghai during the 1920s and 1930s. As China’s gateway to the West, Shanghai was a melting pot of ideas, commerce, and fashion. It was here that the cheongsam transformed from a loose student’s robe into the chic, tailored garment we recognize today. Influenced by Western tailoring techniques and the slim, vertical lines of the Flapper dress, the cheongsam began to be darted at the waist and chest, hugging the body’s curves for the first time in Chinese history.

This new style became synonymous with the “Modern Girl” (modeng xiaojie), a new archetype of Chinese womanhood. She was educated, often financially independent, and socially active. She rode bicycles, went to cinemas, and worked as a teacher, a shopgirl, or a professional. The cheongsam was her perfect attire. It was:

- Practical: More streamlined and less cumbersome than older forms of dress, it allowed for greater freedom of movement.

- Modern: Its form-fitting cut was a bold embrace of the female body, a direct refutation of the old mandate to conceal.

- Uniquely Chinese: While influenced by the West, its mandarin collar, side slits, and frog closures maintained a distinct Chinese identity, allowing women to be modern without being wholly Westernized.

The following table illustrates the dramatic shift in women’s attire and its underlying symbolism:

| Feature | Qing Dynasty Attire (e.g., Ao-qun) | Early Republican Cheongsam (1920s-1930s) |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, layered, body-obscuring. A-line or two-piece. | Streamlined, form-fitting, accentuating the natural body curve. |

| Construction | Flat, two-dimensional cut. | Tailored with darts and set-in sleeves for a three-dimensional fit. |

| Sleeves | Long and wide. | Became progressively shorter, eventually sleeveless. |

| Hemline | Ankle-length, often covering bound feet. | Rose to the calf and sometimes the knee, revealing the legs. |

| Movement | Restrictive and cumbersome. | Side slits were introduced and raised to allow for ease of movement. |

| Symbolism | Modesty, confinement, patriarchal control. | Modernity, independence, liberation, national identity. |

| Wearer’s Role | Primarily domestic, defined by family. | Public-facing student, professional, socialite. |

3. Design as Declaration: Sleeves, Slits, and Social Change

Every modification made to the cheongsam during this period was a small act of rebellion. The shortening of sleeves to expose the arms was a direct challenge to centuries of enforced modesty. The raising of the side slits, which began as a practical measure to facilitate walking, became a daring fashion statement that offered glimpses of the leg. The introduction of new, lighter, and often imported fabrics like rayon democratized the garment, making it accessible beyond the wealthy elite. Even the choice to go braless or wear a soft, unstructured brassiere under the cheongsam was a personal choice that asserted bodily autonomy.

The dress became a canvas upon which women projected their new identities. It was a declaration that their bodies were their own, not objects to be hidden away in shame. By choosing to wear a cheongsam with a higher slit, shorter sleeves, or a more daring pattern, a woman was actively participating in the redefinition of femininity in China. She was claiming her right to be seen, to be fashionable, and to occupy public space with confidence.

4. A National Dress on the World Stage

As the cheongsam’s popularity soared, it transcended its status as a mere fashion item and became the unofficial national dress of the Republic of China. This was powerfully demonstrated by figures like Soong Mei-ling (Madame Chiang Kai-shek). During her tours of the United States in the 1930s and 1940s, her wardrobe of exquisite, custom-made cheongsams presented a powerful image to the world. She appeared as a woman who was sophisticated, articulate, and unmistakably modern, yet profoundly Chinese. The cheongsam, in her hands, became a tool of cultural diplomacy, embodying a nation striving for modernity on its own terms.

The burgeoning Chinese film industry further cemented the cheongsam’s iconic status. Actresses like Ruan Lingyu and Hu Die became fashion plates, their on-screen and off-screen wardrobes inspiring trends across the country. The cheongsam was no longer just a dress; it was a symbol of glamour, aspiration, and a shared national culture. For those interested in a deeper dive into the specific styles worn by these historical figures, platforms like Cheongsamology.com offer detailed analyses and visual archives that connect the evolution of the dress to the women who made it famous.

5. Repression, Survival, and Modern Revival

The cheongsam’s golden age came to an abrupt end with the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Under the Communist Party, the cheongsam was decried as bourgeois, a symbol of the decadent, capitalist West and the feudal past. It was suppressed during the Cultural Revolution, replaced by the unisex, utilitarian Mao suit which aimed to erase class and gender distinctions. The dress of liberation was now itself a target of political repression.

However, the cheongsam did not disappear. It survived and continued to evolve in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and in Chinese diasporic communities around the world. In Hong Kong, it remained a staple of daily wear for many women through the 1960s and became a symbol of a distinct Hong Kong identity. Today, the cheongsam is experiencing a renaissance both within China and globally. It has been re-embraced as a symbol of cultural heritage, often worn at weddings and formal events. Yet, its modern identity is complex. It walks a fine line between being a symbol of cultural pride and empowerment, and at times being fetishized or seen as a costume.

The journey of the cheongsam is a mirror to the complex journey of the Chinese woman in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is a story of breaking free, of self-definition, of political expression, and of the negotiation between tradition and modernity. It began as a bold statement against a patriarchal system, became the uniform of a new, liberated woman, served as a national symbol on the world stage, survived decades of political suppression, and re-emerged as a cherished, if complicated, icon of cultural identity. The cheongsam is far more than a beautiful dress; it is a wearable archive of revolution, a testament to the enduring quest for female emancipation.