The cheongsam, known in Mandarin as the qipao, is more than just a dress; it is a cultural icon, a symbol of feminine elegance, and a historical document woven from silk and thread. Its iconic silhouette—a high-necked, close-fitting dress with an asymmetrical opening and high side slits—is instantly recognizable worldwide. Yet, this celebrated garment has undergone a dramatic and fascinating evolution, mirroring the turbulent social and political transformations of China over the last century. From its origins as a loose, concealing robe for Manchu nobility to its zenith as the uniform of Shanghai’s glamorous socialites and its current status as a global fashion statement, the cheongsam’s story is one of adaptation, identity, and enduring beauty. This article traces the remarkable journey of the cheongsam, exploring its roots, its golden age, its periods of decline, and its powerful modern-day renaissance.

1. Imperial Origins: The Manchu Changpao

The garment we recognize today as the cheongsam did not exist in its form-fitting style until the 20th century. Its true ancestor is the changpao, or “long robe,” of the Manchu people who founded the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Under the “Banner System” of the Qing, all Manchu men, women, and children were required to wear specific clothing to distinguish them from the Han Chinese majority. For women, this was a one-piece, A-line robe that hung straight from the shoulders to the ankles. Its design was functional and modest, intended to conceal the wearer’s figure and accommodate a nomadic, horse-riding lifestyle. These early garments were a far cry from the body-hugging dresses of later years.

| Feature | Qing Dynasty Changpao | Modern Cheongsam |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, A-line, straight cut | Form-fitting, sheath-like |

| Fit | Concealed the body’s shape | Emphasized the body’s curves |

| Sleeves | Long and wide | Varies from long to cap-sleeved or sleeveless |

| Material | Heavy silk, brocade, padded cotton | Silk, satin, lace, cotton, velvet, modern blends |

| Primary Purpose | Ethnic identification, modesty, practicality | Fashion, expressing femininity, formal wear |

The term qipao translates to “banner gown,” a direct reference to the Manchu “Bannermen.” While Han Chinese women continued to wear their traditional two-piece attire (aoqun), the changpao remained a symbol of the ruling class. Its defining features—the high Mandarin collar and the side fastenings—were practical elements that would later be retained and stylized in the modern cheongsam.

2. The Golden Age: Shanghai in the 1920s-1940s

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and the rise of the Republic of China ushered in an era of profound change. As old imperial structures crumbled, so did sartorial rules. It was in the cosmopolitan hub of Shanghai, a city buzzing with Western influence, intellectual ferment, and a burgeoning women’s rights movement, that the cheongsam was born. Young, educated women began to adapt the old Manchu changpao, slimming down its silhouette and shortening it to create a more modern and practical garment. This new dress, initially worn by students and intellectuals, was a symbol of liberation and modernity.

By the 1930s, the cheongsam had become the undisputed queen of Chinese fashion. Shanghai’s tailors, influenced by Western tailoring techniques and Hollywood glamour, transformed the dress into a work of art. The fit became increasingly audacious, hugging the hips and bust to create an hourglass figure. Hemlines rose and fell with global trends, sleeves disappeared in favor of sleeveless or cap-sleeve styles, and the side slits crept higher, adding an alluring-yet-elegant sensuality. The use of the pankou, or decorative frog fastenings, became an art form in itself.

| Decade | Key Style Characteristics | Societal Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1920s | Looser fit, bell-shaped, hemline below the knee, often worn with trousers. | Post-imperial era, rise of student movements, early adoption. |

| 1930s | Increasingly form-fitting, higher collar, higher side slits, sleeveless styles appear. | “Golden Age” of Shanghai, peak of glamour and sophistication. |

| 1940s | More utilitarian designs due to wartime austerity, shorter hemlines, simpler fabrics. | Second Sino-Japanese War and WWII, practicality over extravagance. |

This era cemented the cheongsam’s image as a garment of supreme elegance, famously worn by socialites, movie stars like Ruan Lingyu, and poster girls who graced calendars and advertisements across the city.

3. Diverging Fates: Post-1949 Developments

The Communist victory in 1949 marked a dramatic turning point in the cheongsam’s history. On mainland China, the dress was condemned as a symbol of bourgeois decadence and Western corruption. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), wearing a cheongsam was a politically dangerous act, and the garment all but vanished from public life, replaced by unisex, utilitarian Mao suits.

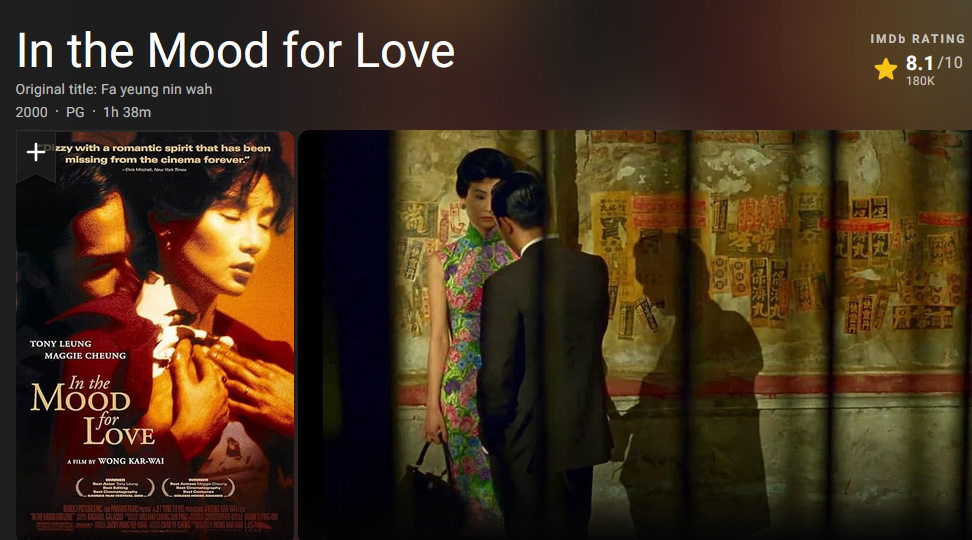

However, as the cheongsam disappeared from the mainland, it flourished elsewhere. Many of Shanghai’s most skilled tailors fled to Hong Kong, which became the new center for cheongsam craftsmanship. In Hong Kong and Taiwan, and among the Chinese diaspora worldwide, the cheongsam was not only daily wear for many women but also a powerful symbol of cultural continuity and identity. The films of director Wong Kar-wai, particularly In the Mood for Love (2000), immortalized this era, showcasing Maggie Cheung in a stunning array of cheongsams that captured the garment’s elegance and emotional resonance.

4. Contemporary Revival and Global Stage

Since China’s economic reforms in the 1980s, the cheongsam has experienced a powerful revival on the mainland. While it is no longer everyday wear, it has been enthusiastically re-embraced for special occasions. Today, it is a popular choice for brides as a traditional wedding gown, worn at formal banquets, and a staple of Chinese New Year celebrations. It has also been adopted as a uniform for hostesses, flight attendants, and diplomats, representing a modern, elegant image of China on the world stage.

Simultaneously, the cheongsam has captivated international fashion designers. Fashion houses like Dior, Tom Ford for YSL, and Ralph Lauren have all drawn inspiration from its iconic silhouette, incorporating elements like the Mandarin collar and asymmetrical opening into their collections. This global exposure has led to a new wave of innovation. Modern designers are deconstructing and reinventing the cheongsam, using non-traditional fabrics like denim and jersey, altering its length, and fusing it with Western design elements. Online platforms and communities, such as the comprehensive resource Cheongsamology.com, meticulously document these contemporary interpretations, creating a digital archive that showcases the garment’s ongoing evolution for a global audience of enthusiasts and scholars.

5. Anatomy of the Cheongsam: The Finer Details

The timeless appeal of the cheongsam lies in its combination of simple lines and intricate details. Understanding these core components is key to appreciating its design.

| Element | Description and Significance |

|---|---|

| Mandarin Collar (立領, lìlǐng) | A stiff, standing collar that is typically 3-5 cm high. It frames the neck gracefully and adds a sense of formality and dignity. |

| Asymmetrical Opening (大襟, dàjīn) | The diagonal opening that runs from the base of the collar across the chest and down the side. It is a defining feature inherited from the changpao. |

| Frog Fastenings (盤扣, pánkou) | Elaborate, knotted buttons made from fabric that secure the opening. They can be simple loops or intricate designs like flowers or insects, serving both functional and decorative purposes. |

| Side Slits (開衩, kāichà) | Slits on one or both sides of the skirt. Originally for ease of movement, they evolved into a key aesthetic element, allowing for a glimpse of the leg and adding to the dress’s allure. |

| Fabric and Motifs | Silk, brocade, and satin are traditional choices. Patterns often carry symbolic meaning, such as dragons for power, phoenixes for good fortune, and peonies for wealth and prosperity. |

These elements work in harmony to create a garment that is at once modest and sensual, traditional and modern, making it a masterpiece of sartorial design.

The cheongsam is a living garment, a thread connecting China’s imperial past to its globalized present. It has been a symbol of ethnic identity, a banner of female liberation, a casualty of political ideology, and a canvas for artistic expression. Its journey from the loose robes of Manchu courts to the runways of Paris and the vibrant streets of modern Shanghai is a testament to its resilience and its profound cultural significance. More than just a piece of clothing, the cheongsam is a narrative of China itself—a story of tradition, transformation, and a beauty that continues to captivate and evolve with each passing generation.