The cheongsam, also known as the qipao, stands as one of the most iconic and recognizable garments in the world. With its elegant silhouette, high mandarin collar, and delicate frog fastenings, it is a potent symbol of Chinese femininity and cultural identity. However, the dress we recognize today is a relatively modern invention, the result of a fascinating evolution that mirrors the dramatic social, political, and cultural shifts of China over the last century. Its journey from a loose-fitting Manchu robe to a form-fitting global fashion statement is a story of tradition meeting modernity, and of a garment’s power to reflect and shape a nation’s identity. This article delves into the rich history of the cheongsam, tracing its transformation through dynastic changes, republican revolutions, and its eventual revival as a timeless piece of heritage.

1. Origins in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

The roots of the cheongsam lie in the Qing Dynasty, founded by the Manchu people from the northeast. The name itself, “qipao” (旗袍), translates to “banner gown,” a direct reference to the Manchu “Banner System” (八旗), a social and military structure. The original garment, known as the changpao (长袍), was worn by both Manchu men and women. It was a far cry from the body-hugging dress of later years.

The early qipao was a long, A-line robe that hung straight from the shoulders, completely concealing the wearer’s figure. It was designed for practicality, suited for the equestrian lifestyle and cold climate of the Manchurian homeland. Its key features included a straight cut, long, wide sleeves, and a length that reached the ankles. It was typically made from robust materials like silk, cotton, or fur-lined fabrics and was fastened with a series of simple toggles along the right-hand side. This garment was not just clothing; it was a powerful symbol of Manchu identity, enforced upon the Han Chinese population during the Qing era as a sign of allegiance to the ruling dynasty.

| Feature | Original Qing Dynasty Qipao/Changpao | Modern Cheongsam (Golden Age) |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, A-line, straight cut | Body-hugging, form-fitting |

| Length | Ankle-length or longer | Varies (calf, knee, or thigh-length) |

| Sleeves | Long and wide | Sleeveless, capped, or short sleeves |

| Slits | Low side slits for movement (horse riding) | High side slits for allure and ease |

| Material | Heavy silk, cotton, fur-lined fabrics | Light silk, satin, brocade, lace, cotton |

| Purpose | Daily wear, symbol of Manchu status | Symbol of modernity, formal wear |

2. The Republic of China and the Birth of the Modern Cheongsam (1910s-1920s)

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and the establishment of the Republic of China heralded an era of profound change. The nation was swept up by the New Culture Movement, which championed Western concepts of science, democracy, and individual freedom, including women’s liberation. As old imperial structures crumbled, so did the rigid dress codes associated with them.

It was in this fertile ground of social change, particularly in cosmopolitan cities like Shanghai and Beijing, that the modern cheongsam was born. Educated women, students, and urbanites sought a new style of dress that reflected their modern identity. They began to adapt the old changpao. The first modifications were subtle. The silhouette became more slender, though still relatively loose compared to what would follow. The garment was streamlined, with the voluminous sleeves narrowed and the overall cut simplified. This new one-piece dress was seen as a practical and elegant alternative to the traditional two-piece aoqun (blouse and skirt) worn by Han women. It became a symbol of the “modern girl,” representing education, independence, and a break from feudal traditions.

3. The Golden Age of Shanghai (1930s-1940s)

The 1930s and 1940s are widely considered the golden age of the cheongsam, with Shanghai as its undisputed epicenter. As the “Paris of the East,” Shanghai was a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures, and its fashion scene was vibrant and innovative. Here, the cheongsam underwent its most dramatic transformation, evolving into the iconic, sensual dress we are familiar with today.

Tailors in Shanghai, influenced by Western dressmaking techniques, began to incorporate darts and shaping to create a garment that celebrated the female form. The silhouette became increasingly body-hugging, accentuating the waist and hips. New, daring features were introduced:

- High Slits: The side slits, once a purely functional feature, were raised, sometimes to the thigh, adding a previously unseen element of allure and glamour.

- Sleeve Variations: Sleeves were shortened to cap sleeves or disappeared entirely, reflecting Western trends.

- Collar and Fastenings: The Mandarin collar remained a key feature but its height varied with fashion. The intricate, handmade frog fastenings, or pankou (盘扣), became a prominent decorative element, crafted into elaborate floral or geometric designs.

- Fabrics and Patterns: New materials like sheer voiles, printed cottons, and luxurious velvets were used alongside traditional silks and brocades. Art Deco-inspired geometric patterns became popular, blending Chinese motifs with Western aesthetics.

The cheongsam was no longer just a dress; it was a canvas for self-expression, worn by everyone from movie stars and socialites to schoolgirls and office workers. Its popularity was fueled by calendar posters, advertisements, and the burgeoning Chinese film industry, cementing its status as the quintessential modern Chinese dress.

| Key Feature (Shanghai Style) | Description |

|---|---|

| Cut | Form-fitting, often with darts at the bust and waist. |

| Collar | High Mandarin collar, varying in height from low to very high. |

| Fastenings | Asymmetrical opening on the right side with elaborate pankou (frog) closures. |

| Sleeves | Ranged from long and bell-shaped to short, capped, or entirely sleeveless. |

| Slits | High side slits became a defining feature. |

| Materials | Wide range, including silk, satin, brocade, velvet, lace, and printed cottons. |

4. Divergence and Decline (1950s-1970s)

The rise of the Communist Party and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 marked an abrupt end to the cheongsam’s reign in mainland China. The new government viewed the form-fitting, elegant dress as a symbol of bourgeois decadence, Western capitalism, and the “old society” it sought to dismantle. It was swiftly replaced by austere, unisex, and utilitarian clothing, most notably the Zhongshan suit (or “Mao suit”). During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), wearing a cheongsam could lead to public humiliation and persecution, and countless beautiful garments were destroyed.

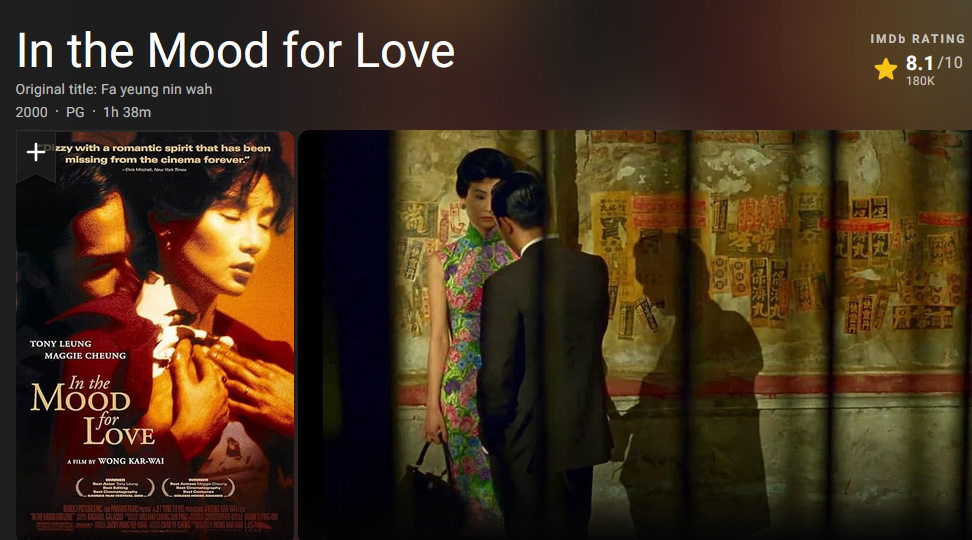

While the cheongsam disappeared from the mainland, its legacy was carried on by the Chinese diaspora. In Hong Kong, which remained a British colony, the dress continued to be worn and evolved. It became standard work attire for many women, often made with more practical fabrics and a slightly more modest cut. Hong Kong cinema of the era, particularly the films of director Wong Kar-wai like “In the Mood for Love,” would later re-popularize the Hong Kong-style cheongsam globally, showcasing its timeless elegance and melancholic beauty. Similarly, in Taiwan and Southeast Asian Chinese communities, the cheongsam remained a cherished garment for formal occasions and celebrations.

5. The Modern Revival and Global Influence (1980s-Present)

Following China’s “Reform and Opening-up” policy in the late 1970s and 1980s, the mainland began to slowly rediscover its cultural heritage. The cheongsam made a gradual comeback, initially as uniforms for women in the hospitality and aviation industries, and then as formal attire for diplomatic events. It was re-embraced as a symbol of national pride and cultural elegance.

In the 21st century, the cheongsam has achieved global status. International fashion designers like Tom Ford, Christian Dior, and Ralph Lauren have frequently incorporated its elements—the Mandarin collar, asymmetrical fastening, and side slits—into their collections. It has become a red-carpet staple for both Chinese and Western celebrities, solidifying its place in the lexicon of global fashion.

Today, the cheongsam is rarely worn as daily attire. Instead, it is reserved for special occasions like weddings, the Lunar New Year, and formal parties. Contemporary designers and boutique brands, many of which are celebrated on platforms like Cheongsamology.com, are dedicated to reinventing the garment for a modern audience. They experiment with unconventional fabrics like denim, knit, and leather, and innovate with new cuts, such as A-line skirts, asymmetrical hemlines, and two-piece ensembles, ensuring that the cheongsam continues to evolve while honoring its rich history.

| Era | Primary Usage and Status |

|---|---|

| 1930s-1940s | Daily wear for all classes; a symbol of modern fashion. |

| 1950s-1970s | Suppressed in mainland China; preserved in Hong Kong, Taiwan, etc. |

| 1980s-Present | Revived as formal wear, ceremonial dress, and a symbol of cultural heritage. |

From its humble beginnings as a functional Manchu robe to its pinnacle as the glamorous uniform of Shanghai’s golden age, the cheongsam has been on a remarkable journey. It has survived political suppression and cultural revolutions to emerge as a cherished symbol of Chinese culture and timeless elegance. Its evolution is a testament to the resilience of tradition and its ability to adapt, absorb, and innovate. The cheongsam is more than just a dress; it is a story woven in silk, a narrative of a nation’s identity that continues to captivate and inspire the world. As it continues to be reinterpreted by new generations, the cheongsam secures its legacy not as a relic of the past, but as a living, breathing piece of fashion history.