The cheongsam, or qipao, is more than just a dress; it is a silken thread woven through the tumultuous history of 20th-century China. Its elegant lines and iconic silhouette evoke images of glamour, resilience, and a distinctly modern Chinese femininity. While its origins are rooted in the final days of the Qing Dynasty, the cheongsam as we know it today was truly born in the cosmopolitan crucible of Shanghai in the 1920s. However, its story did not end there. Forced by political upheaval, the garment, along with its master craftsmen, embarked on a journey south to the British colony of Hong Kong, where it was not only preserved but transformed, enjoying a second golden age. This is the story of that migration—a tale of how a single garment adapted, evolved, and came to symbolise the spirit of two of Asia’s most dynamic cities.

1. The Birthplace: Shanghai’s Golden Age (1920s-1940s)

In the early decades of the 20th century, Shanghai was the “Paris of the East,” a vibrant treaty port humming with international trade, new ideas, and social change. It was here that the modern cheongsam emerged from its predecessor, the loose, straight-cut changpao. As Chinese women, influenced by Western ideals of liberation and fashion, began to enter public life, they sought a garment that was both modern and distinctly Chinese.

The early Shanghai cheongsam was relatively modest, featuring a high collar, a loose A-line cut, and wide sleeves, often resembling a slightly tailored version of the traditional robe. However, by the 1930s, it had evolved dramatically. Shanghai’s tailors, absorbing Western sartorial techniques, began to craft the dress to be form-fitting, accentuating the natural curves of the body. The silhouette became slender, side slits crept higher, and sleeves became shorter or disappeared entirely. It was a bold statement of modernity and confidence. Made from luxurious silks, brocades, and velvets, and adorned with intricate pankou (frog closures), the Shanghai cheongsam became the uniform of the city’s elite—socialites, movie stars, intellectuals, and modern urban women.

| Feature | Early Shanghai Cheongsam (c. 1920s) | Peak Shanghai Cheongsam (c. 1930s-40s) |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, A-line, straight-cut | Form-fitting, body-hugging, slender |

| Collar | High, stiff collar | High collar, sometimes lower for comfort |

| Sleeves | Bell-shaped, wrist- or elbow-length | Short, cap-sleeved, or sleeveless |

| Slits | Low or no side slits | High side slits, often reaching the thigh |

| Materials | Silk, cotton | Imported silk, lace, velvet, brocade |

| Symbolism | Emerging modernity, post-imperial identity | Sophistication, glamour, feminine liberation |

2. The Exodus: Political Turmoil and the Migration of Skill

The golden age of Shanghai was brought to an abrupt end by war and revolution. The Japanese invasion followed by the Chinese Civil War culminated in the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Under the new Communist government, the cheongsam, with its association with bourgeois decadence and Western influence, was officially discouraged. Simplicity and austerity, embodied by the unisex “Mao suit,” became the new sartorial ideal.

Faced with this new political reality, a wave of people fled the mainland. Among them were Shanghai’s most affluent citizens, industrialists, and, crucially, its community of master tailors. They sought refuge in the British-controlled colony of Hong Kong, bringing with them not only their wealth but their invaluable skills and craftsmanship. This migration ensured that the art of cheongsam making, which faced extinction on the mainland, would find a new home where it could survive and flourish.

3. The New Haven: Hong Kong’s Reinvention (1950s-1960s)

In post-war Hong Kong, the transplanted Shanghainese tailors set up shop and began to cater to a new clientele. The city was a bustling hub of commerce and a unique crossroads of Eastern and Western cultures. Here, the cheongsam underwent a second, distinct evolution, adapting to the climate, lifestyle, and aesthetic sensibilities of its new environment.

The Hong Kong cheongsam became more practical and integrated with Western tailoring. While the Shanghai style was often a statement piece for the elite, the Hong Kong version became a form of daily wear for women from all walks of life. Key transformations included:

- Integration of Western Techniques: Tailors incorporated darts at the bust and waist to create an even more sculptural, hourglass figure, influenced by Christian Dior’s “New Look” that was sweeping the West. Zippers often replaced the full-length side openings of traditional pankou, making the garment easier to wear.

- Practical Materials: While silk remained popular for formal occasions, tailors began using more durable and affordable fabrics like cotton, linen, and later, synthetic blends like polyester, for everyday cheongsams suitable for Hong Kong’s humid climate.

- A More Severe Cut: The Hong Kong cheongsam was often characterised by a starker, more minimalist elegance. The silhouette was taut, the lines clean, and embellishments were often kept to a minimum, placing full emphasis on the perfect fit and the woman’s figure.

| Aspect | Shanghai Cheongsam (1930s-40s) | Hong Kong Cheongsam (1950s-60s) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Influence | Chinese tradition meets Art Deco modernity | Shanghainese skill meets Western tailoring |

| Fit | Sensuously form-fitting, draped | Structurally form-fitting, using darts and zippers |

| Fastenings | Predominantly pankou (frog closures) | Combination of pankou and concealed zippers |

| Materials | Luxurious fabrics (silk, velvet, lace) | Broader range, including cotton and synthetics |

| Typical Occasion | Social events, formal functions | Daily wear, work uniform, formal events |

| Cultural Symbolism | Cosmopolitan glamour, avant-garde | Pragmatic elegance, East-meets-West identity |

4. The Cheongsam in Cinema and Culture

Cinema played a pivotal role in cementing the iconic status of the cheongsam in both cities. In 1930s Shanghai, film stars like Ruan Lingyu and Hu Die popularised the garment, making it an aspirational symbol for millions.

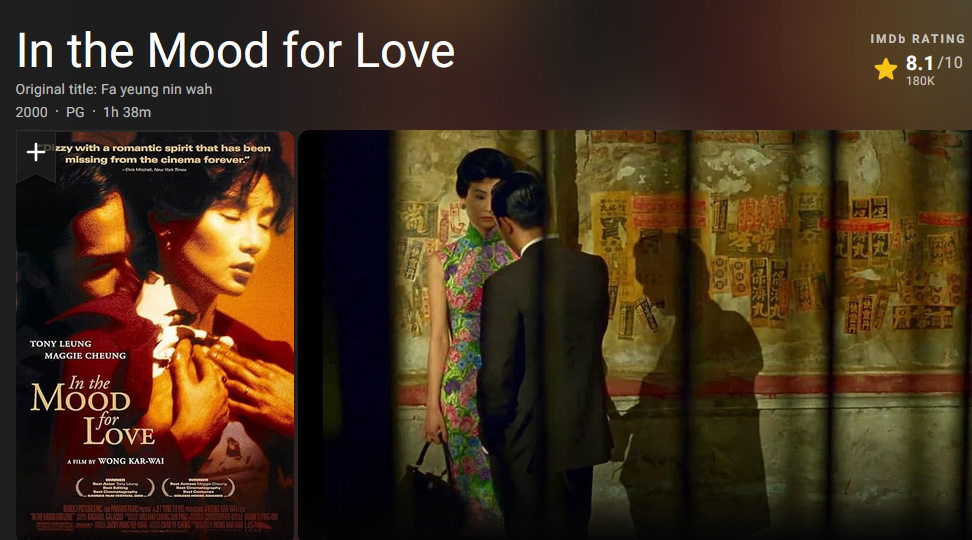

However, it was in Hong Kong cinema that the cheongsam found its most enduring cinematic expression. Director Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece, In the Mood for Love (2000), is a veritable love letter to the Hong Kong cheongsam of the 1960s. Maggie Cheung’s character wears a stunning succession of meticulously tailored cheongsams, each one reflecting her shifting emotions. The high, stiff collar and constrained fit of her dresses symbolise her repression and grace, turning the garment into a central narrative device. The film single-handedly sparked a global resurgence of interest in the cheongsam, forever associating it with an aura of timeless elegance, nostalgia, and restrained passion.

5. Decline and Modern Revival

By the late 1960s and 1970s, the cheongsam’s role as daily wear in Hong Kong began to wane. Mass-produced Western fashions like jeans, mini-skirts, and T-shirts offered greater convenience and became the dominant choice for younger generations. The cheongsam was relegated to a more ceremonial role, worn primarily for weddings, formal banquets, and as uniforms for service staff in high-end hotels and restaurants.

In recent decades, however, there has been a significant revival. Both in mainland China and across the global diaspora, there is a renewed appreciation for the cheongsam as a powerful symbol of cultural heritage. Contemporary designers are reinterpreting the classic form with modern fabrics, new cuts, and innovative designs. Enthusiast communities and online platforms, such as Cheongsamology.com, play a vital role in this revival by documenting the garment’s history, sharing tailoring techniques, and creating a space for a new generation to connect with its legacy. The cheongsam is no longer just a vintage curiosity; it is a canvas for modern expression that continues to evolve.

The journey of the cheongsam from the ballrooms of Shanghai to the bustling streets of Hong Kong is a powerful metaphor for the resilience of culture. It is a story of how craftsmanship and tradition, when faced with displacement, did not fade away but instead adapted, absorbed new influences, and created something new and beautiful. The cheongsam is not a static relic of the past but a living garment whose elegant lines carry the weight of history, the spirit of innovation, and the enduring identity of Chinese women across the world. Its evolution continues, ensuring that its silken thread will be woven into the fabric of the future.