The cheongsam, or qipao, is more than just a garment; it is a vessel of history, a canvas for artistry, and a powerful symbol of identity. Its slender, form-fitting silhouette is instantly recognizable, evoking notions of elegance, tradition, and sensuality. Nowhere has its multifaceted nature been more vividly explored and, at times, controversially defined, than on the silver screen. For decades, cinema has used the cheongsam as a potent visual shorthand, reflecting and shaping global perceptions of Chinese femininity and culture. By tracing its journey from the exoticized allure of The World of Suzie Wong to the empowered statement of Crazy Rich Asians, we can map a broader evolution in the representation of Asian identity in film—a journey from objectification to agency, from stereotype to nuanced self-definition.

1. The Shanghai Golden Age: The Cheongsam’s Authentic Roots

Before the cheongsam was adopted by Hollywood, it was the definitive dress of a modernizing China. Born in the cosmopolitan crucible of 1920s Shanghai, the qipao evolved from the loose-fitting robes of the Manchu nobility into a sleek, body-hugging garment that symbolized the “New Woman.” She was educated, socially mobile, and breaking free from feudal constraints. Early Chinese cinema celebrated this. Actresses like Ruan Lingyu and “Butterfly” Wu became national icons, and their on-screen cheongsams were emblematic of a newfound glamour and independence. In these films, the cheongsam was not an exotic costume but a contemporary uniform of elegance, worn by women navigating the complexities of a rapidly changing society. It was a symbol of Chinese modernity, for a Chinese audience.

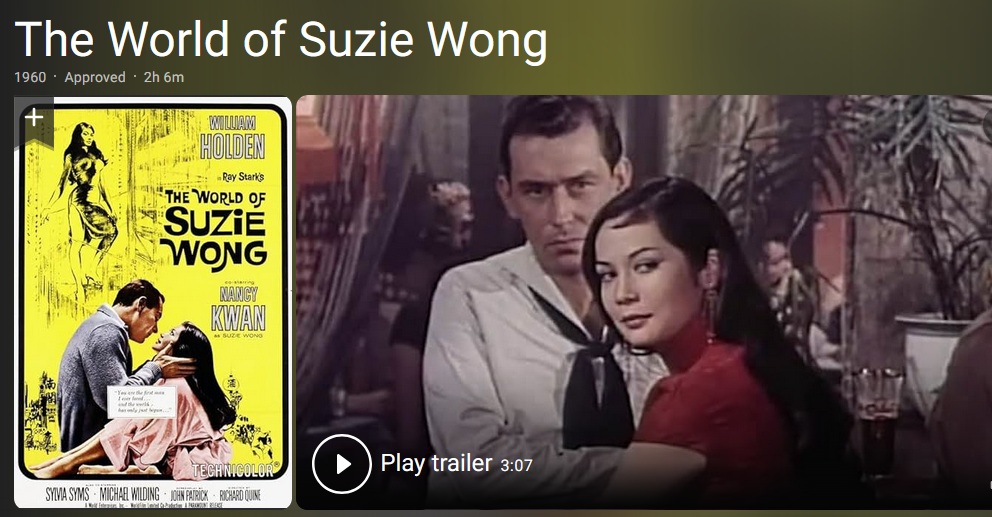

2. The Western Gaze: Exoticism and the “Suzie Wong” Trope

When the cheongsam entered the Western cinematic imagination, its meaning was profoundly altered. The watershed moment was the 1960 film The World of Suzie Wong, starring Nancy Kwan. Set in Hong Kong, the film tells the story of a charming prostitute with a heart of gold who captivates a white American artist. Kwan’s wardrobe consists almost entirely of a vibrant collection of cheongsams. While visually stunning, these garments served to package her character for the Western male gaze. The cheongsam became a uniform of the “other”—exotic, sensual, and ultimately, available. The high slit, originally designed for ease of movement, was exaggerated to emphasize sexuality. This portrayal cemented the cheongsam in Western minds as a symbol tied to one of two prevailing stereotypes: the submissive “Lotus Blossom” or the dangerously seductive “Dragon Lady.”

| Aspect | Original Shanghai Context | “The World of Suzie Wong” Context |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolism | Modernity, liberation, elegance, national pride | Exoticism, sensuality, subservience, foreignness |

| Cut & Fit | Modest yet fashionable, tailored to the individual | Often exaggeratedly tight with a high slit to emphasize sexuality |

| Character Type | The “New Woman”: educated, independent, modern | The “Lotus Blossom”: a beautiful, tragic, and available object of desire |

| Intended Audience | Primarily Chinese audiences | Primarily Western audiences |

This trope persisted for decades, with the cheongsam appearing in countless films, from the James Bond franchise to various Hollywood action movies, often worn by characters who were either villainous femme fatales or damsels in distress.

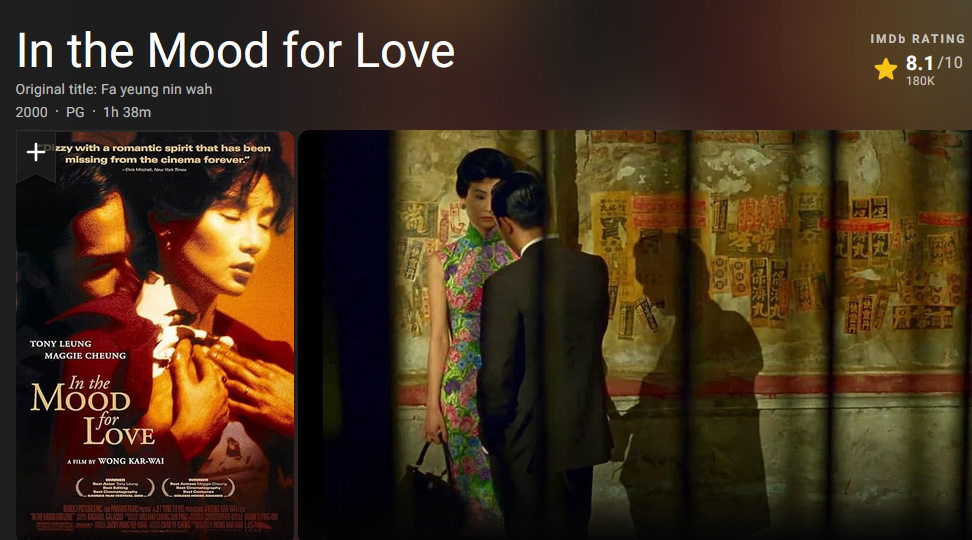

3. Reclaiming the Narrative: Wong Kar-wai’s Visual Poetry

The cinematic reclamation of the cheongsam began in earnest with Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece, In the Mood for Love (2000). Set in 1960s Hong Kong, the same era as Suzie Wong, the film presents a starkly different vision. The protagonist, Su Li-zhen (played by Maggie Cheung), wears over twenty different cheongsams throughout the film, each one a work of art. However, these are not garments of seduction. Instead, they function as a kind of emotional armor. The impossibly high, stiff collars and restrictive fit mirror her repressed desires, her loneliness, and the suffocating social decorum that traps her and her neighbour, Chow Mo-wan. The fabric and pattern of each dress change with the mood and passage of time, becoming a silent narrator of her inner turmoil. Wong Kar-wai stripped the cheongsam of its Western-imposed exoticism and restored its dignity, using it as a tool of profound character study and visual poetry. For those interested in the intricate details of the film’s costuming, from the specific floral prints to the tailoring techniques, dedicated resources like Cheongsamology.com provide exhaustive analysis of how each garment contributes to the film’s narrative.

4. Agency and Action: The Cheongsam in a New Light

Following In the Mood for Love, other filmmakers began to explore the cheongsam’s potential with greater nuance. In Ang Lee’s espionage thriller Lust, Caution (2007), the cheongsams worn by Tang Wei’s character are central to her mission. They are tools of her trade as a spy, meticulously chosen to seduce, project an image of sophistication, and infiltrate high society. Here, the sensuality of the dress is not for the pleasure of a passive gaze but is actively weaponized by a woman with clear agency, even if her mission ultimately consumes her. The garment is a costume, but one she chooses to wear as part of a deadly performance. This portrayal moved the cheongsam beyond a mere symbol of beauty or oppression and into the realm of female power and strategy.

The table below highlights the shifting portrayals of the cheongsam in key films.

| Film Title | Year | Key Character | Cheongsam’s Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| The World of Suzie Wong | 1960 | Suzie Wong (Nancy Kwan) | A uniform of exoticism and sexual availability for the Western gaze. |

| In the Mood for Love | 2000 | Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) | A symbol of repressed emotion, elegance, loneliness, and suffocating beauty. |

| Lust, Caution | 2007 | Wong Chia Chi (Tang Wei) | A strategic tool of espionage and seduction; a costume for a performance of power. |

| Crazy Rich Asians | 2018 | Eleanor Young & Rachel Chu | A dual symbol: traditional authority (Eleanor) and modern, self-defined identity (Rachel). |

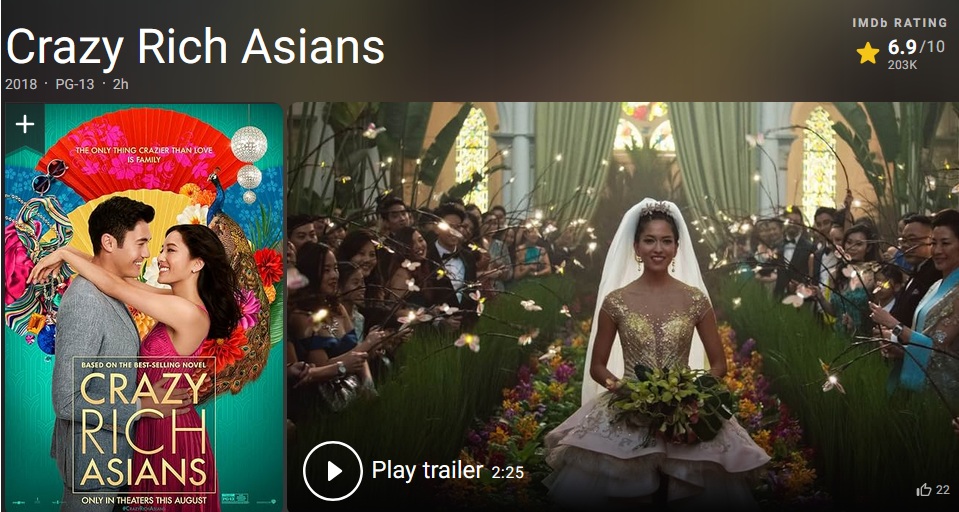

5. Full Circle: Power and Identity in “Crazy Rich Asians”

The journey of the cinematic cheongsam comes full circle in the blockbuster hit Crazy Rich Asians (2018). The film masterfully uses the garment to explore themes of tradition, modernity, and cultural identity across generations. The formidable matriarch, Eleanor Young (Michelle Yeoh), wears classic, impeccably tailored cheongsams that project authority, wealth, and an unwavering commitment to tradition. Her cheongsams are her armor, signifying her role as the guardian of her family’s legacy.

In contrast, the protagonist, Chinese-American Rachel Chu (Constance Wu), initially dresses in Western styles, symbolizing her cultural disconnect. Her pivotal moment of self-actualization comes during the climactic mahjong scene. For this confrontation with Eleanor, she wears a stunning, pale blue dress that is clearly inspired by a cheongsam but is modern in its cut and design. It is not a costume forced upon her, but a choice. By wearing it, Rachel signals that she is embracing her heritage, but on her own terms. She is not Suzie Wong, an object of fantasy, nor is she Su Li-zhen, a figure of beautiful tragedy. She is a modern, confident woman bridging two cultures, and her cheongsam is a declaration of this hybrid, empowered identity.

The cheongsam, once used by Hollywood to define and confine the Asian woman, has been triumphantly reclaimed on screen. Its cinematic evolution mirrors a broader struggle for authentic representation, moving from a one-dimensional trope to a complex and multifaceted symbol. The journey from the back alleys of Suzie Wong’s Hong Kong to the opulent halls of the Young family Singapore is not just a story about a dress. It is the story of how cinema has slowly learned to see the women who wear it not as exotic objects, but as the powerful, nuanced, and self-defining subjects they have always been. The cheongsam remains an icon, but its meaning is no longer dictated by others; it is now defined by the women who wear it, both on screen and off.