The cheongsam, or qipao, is one of the most iconic and instantly recognizable garments in the world. With its elegant high collar, form-fitting silhouette, and alluring side slits, it embodies a unique blend of traditional Chinese aesthetics and modern sensuality. Yet, this celebrated dress is not an ancient relic from imperial dynasties; rather, it is a distinctly 20th-century creation whose evolution is deeply intertwined with the turbulent social, political, and cultural transformations of modern China. From its origins as a loose robe to its glamorous heyday in Shanghai, its suppression during the Cultural Revolution, and its triumphant global revival, the history of the cheongsam is the story of the Chinese woman stepping into a new era.

1. Origins and Etymological Roots

The term “cheongsam” and “qipao” are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct origins that hint at the garment’s complex history. The word qipao (旗袍) literally translates to “banner gown.” It refers to the clothing worn by the Manchu people, who were organized into “banners” (旗, qí) and who founded the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). The original qipao was a long, loose, A-line robe worn by both men (changpao) and women. It was designed for practicality, especially for horse riding, and its primary purpose was to conceal the wearer’s figure and signify their ethnic identity.

The term cheongsam (長衫) is Cantonese and simply means “long dress.” When the modern, form-fitting version of the dress gained popularity in Shanghai in the 1920s, it spread to southern China, including Cantonese-speaking regions like Hong Kong. There, it was known as the cheongsam. Due to the significant influence of Hong Kong cinema and tailoring, this term became widely known in the West. Today, qipao is more commonly used in Mandarin-speaking regions, while cheongsam is prevalent in English and Cantonese.

| Feature | Traditional Manchu Qipao (Changpao) | Modern Cheongsam (Post-1920s) |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, A-line, straight | Form-fitting, body-hugging, sheath |

| Cut | One-piece, wide cut | Often darted and tailored for shape |

| Material | Heavy silk, cotton, fur-lined for warmth | Silk, brocade, satin, rayon, velvet, lace |

| Slits | Slits on front, back, and sides for horse riding | Primarily side slits for movement and style |

| Purpose | Everyday wear, indicated ethnic status | Formal wear, fashion statement, symbol of modernity |

| Gender | Worn by both men and women | Exclusively a female garment |

2. The Birth of the Modern Cheongsam in Republican China

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and the establishment of the Republic of China marked a seismic shift in Chinese society. There was a fervent desire to break from the feudal past and embrace modernity. This sentiment extended to fashion. Educated women, intellectuals, and students began to seek a new style of dress that was both Chinese and modern, rejecting the cumbersome robes of the imperial era.

Initially, in the late 1910s and early 1920s, a transitional garment emerged. It was a looser, bell-shaped version of the cheongsam, often worn over trousers, resembling the male changpao but with wider sleeves and decorative elements. It became a symbol of the burgeoning women’s liberation movement, as it was adopted by students in the newly established schools for girls. It represented freedom from the restrictive clothing of the past and a step towards public life.

The true transformation occurred in the cosmopolitan hub of Shanghai. Influenced by Western tailoring and the slim, vertical lines of 1920s flapper dresses, the cheongsam began to evolve rapidly. Tailors started to incorporate darts and use more sophisticated cutting techniques to create a dress that followed the contours of the female body. The hemline rose, the fit tightened, and the garment began to be worn on its own, without trousers. This new, streamlined cheongsam was a radical statement of modernity and female empowerment.

3. The Golden Age: Shanghai Glamour from the 1930s to 1940s

The 1930s and 1940s are universally considered the golden age of the cheongsam, with Shanghai as the undisputed capital of its evolution. The city was a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures, and its fashion scene was vibrant and innovative. The cheongsam became the canvas upon which the era’s glamour was painted.

During this period, the silhouette became even more daringly form-fitting, emphasizing the waist and hips. Stylistic variations flourished, driven by socialites, movie stars, and fashion magazines.

| Decade | Hemline | Fit | Collar | Sleeves | Slits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920s | Calf to ankle-length | Loosening from A-line, slightly straight | Medium to high | Wide, often bell-shaped | Low to non-existent |

| 1930s | Fluctuated, often long, near the floor | Increasingly form-fitting, body-hugging | Very high, sometimes reaching the chin | Cap sleeves, short sleeves, or sleeveless | Rose to the thigh, became a key feature |

| 1940s | Rose to just below the knee | Still form-fitting, more practical elements | Became lower and more comfortable | Short sleeves and cap sleeves common | Remained high, often to the upper thigh |

Designers experimented with Western fabrics like velvet, lace, and sheer chiffon, alongside traditional silks and brocades. Art Deco patterns, geometric prints, and bold floral motifs became popular. The iconic diagonal opening (xie jin) was secured with intricate handmade frog fasteners (pankou), which became a signature decorative element. The cheongsam of this era was a symbol of sophistication, worn by everyone from glamorous film stars like Ruan Lingyu to everyday urban women.

4. Suppression on the Mainland and Survival in Hong Kong

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 brought the golden age to an abrupt end. The Communist government viewed the cheongsam as a symbol of bourgeois decadence, Western influence, and the feudal past. It was actively discouraged and effectively disappeared from public life on the mainland. In its place, the austere, unisex Mao suit (Zhongshan suit) became the standard attire, promoting ideals of revolutionary simplicity and gender equality through conformity.

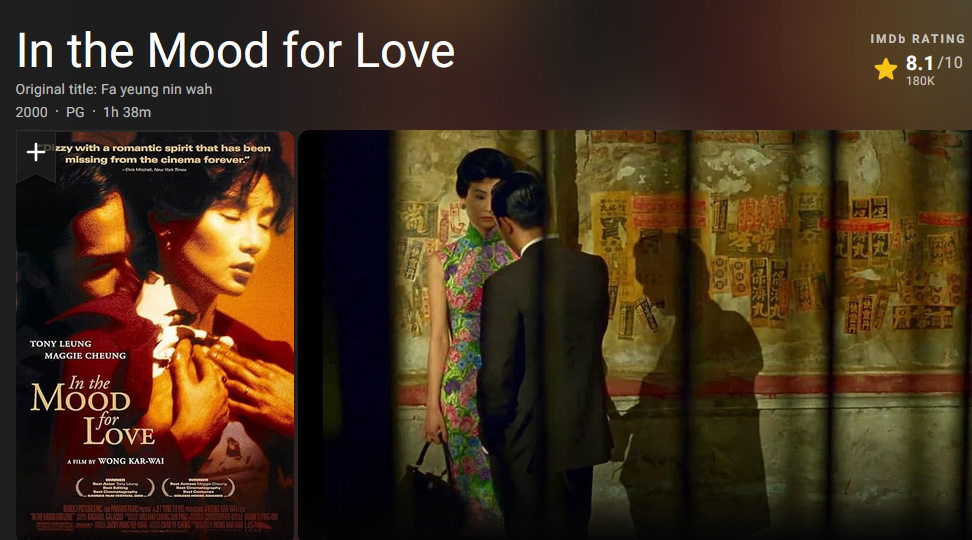

While the cheongsam vanished from mainland China, it found a new home in Hong Kong. Many skilled Shanghai tailors fled to the British colony, bringing their craft with them. In Hong Kong, the cheongsam continued to thrive throughout the 1950s and 1960s as everyday wear. It was adapted for a modern, working lifestyle, often made with more durable fabrics and slightly less restrictive cuts. It was famously worn by Maggie Cheung’s character in the film In the Mood for Love (2000), which single-handedly romanticized the 1960s Hong Kong cheongsam for a new generation. Elsewhere, in Taiwan and in overseas Chinese communities, the dress was preserved as a formal garment for special occasions.

5. Global Renaissance and Modern Interpretation

Beginning in the 1980s, with China’s economic “Reform and Opening Up,” the cheongsam began a slow and steady comeback on the mainland. Initially seen only at weddings and formal events, it gradually re-entered the cultural consciousness as a symbol of national pride and heritage.

The true global renaissance, however, was fueled by international media and fashion. Films like The Last Emperor (1987) and The Joy Luck Club (1993) introduced its elegance to Western audiences. International fashion designers like John Galliano, Tom Ford for Yves Saint Laurent, and Ralph Lauren began incorporating elements of the cheongsam—the mandarin collar, frog fasteners, and side slits—into their collections.

In the digital age, the appreciation for the cheongsam has grown exponentially. Enthusiasts, designers, and historians now have platforms to share knowledge and celebrate the garment’s legacy. For instance, resources like the website Cheongsamology.com serve as dedicated hubs for the academic study and cultural appreciation of the dress, connecting a global community of admirers and makers. Modern interpretations abound, from casual cotton cheongsams worn with sneakers to deconstructed versions paired with jeans, proving its remarkable adaptability.

The cheongsam is no longer just one thing. It is at once a formal dress for diplomats, a wedding gown, a high-fashion statement, and a symbol of cultural identity. It continues to evolve, demonstrating that its timeless elegance is capable of being reinterpreted by each new generation.

The journey of the cheongsam is a mirror reflecting the dramatic story of modern China. It has traversed a century of change, embodying the spirit of the modern Chinese woman in her quest for identity—from the bold intellectual of the Republican era to the glamorous starlet of Shanghai, the resilient keeper of tradition in Hong Kong, and the confident global citizen of today. More than just a piece of clothing, the cheongsam is a powerful cultural artifact, a testament to the enduring power of elegance, resilience, and style. Its high collar and graceful lines carry the weight of history, while its ever-changing form looks confidently toward the future.