The cheongsam, or qipao, is far more than a mere article of clothing. With its high mandarin collar, fitted silhouette, and delicate pankou (frog closures), it is a garment woven into the very fabric of modern Chinese history. It is a potent cultural symbol, a canvas upon which narratives of modernity, tradition, revolution, and identity have been projected. Emerging from the dynamic, cosmopolitan ferment of 1920s Shanghai, the cheongsam has lived many lives: as the uniform of the liberated “New Woman,” a relic of bourgeois decadence, a nostalgic emblem of a lost homeland, and a contested marker of femininity. In Chinese and diasporic literature, this iconic dress transcends its material form, becoming a powerful literary device that authors use to explore the complex inner lives of their characters and the sweeping historical forces that shape them. Its presence—or even its conspicuous absence—on the page can speak volumes, revealing tensions between the individual and society, the past and the present, and the homeland and the diaspora.

1. The Modernist Manifesto: The Cheongsam in Republican Shanghai

The golden age of the cheongsam, from the 1920s to the 1940s, coincided with a period of immense social and cultural upheaval in China. In the bustling metropolis of Shanghai, the cheongsam evolved from a looser, more modest garment into the form-fitting dress recognized today. For writers of this era, the cheongsam became the quintessential symbol of the “New Woman” (新女性)—educated, independent, and publicly visible. It was a sartorial declaration of freedom from the feudal, binding clothes of the past.

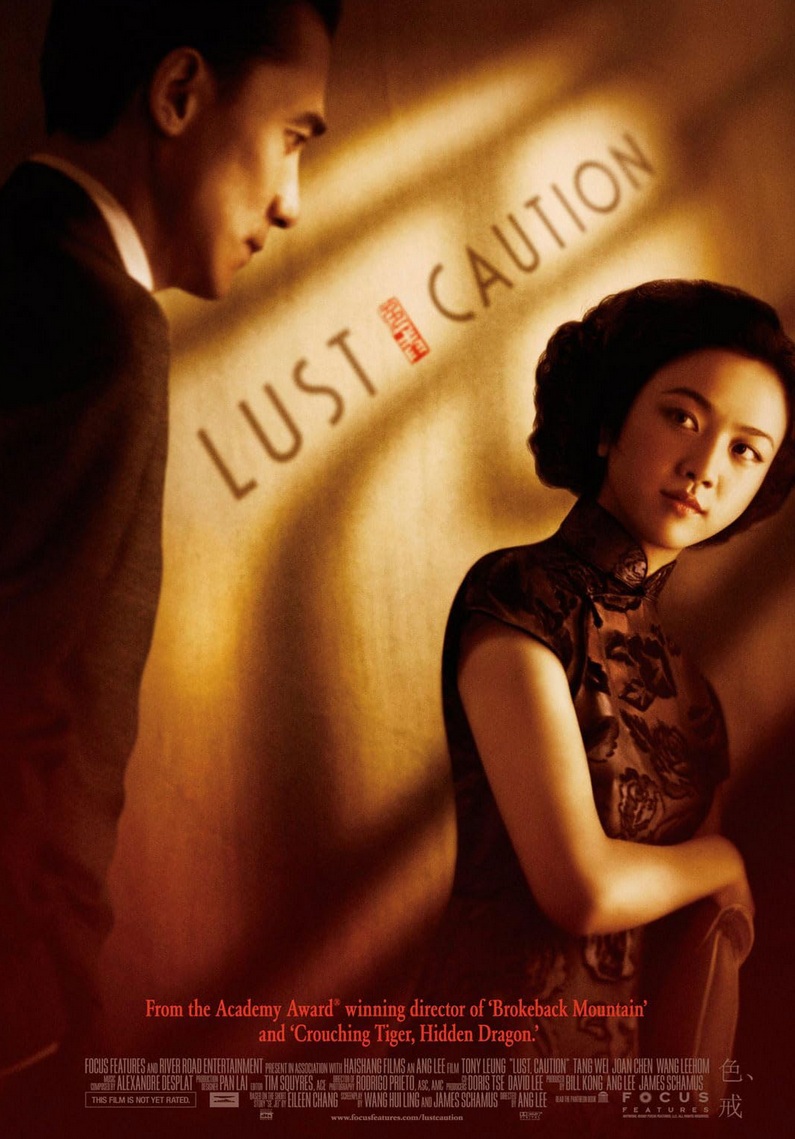

No author captured the intricate relationship between a woman and her cheongsam more astutely than Eileen Chang (张爱玲). In her work, clothing is never just decorative; it is a second skin that reveals a character’s desires, deceptions, and social standing. In her celebrated novella, Lust, Caution (色,戒), the cheongsams worn by the protagonist, Wang Jiazhi, are central to her transformation from a naive student into a sophisticated spy. Her meticulously described dresses are her armor and her weapon. A simple, school-girl blue cheongsam signifies her initial innocence, while the seductive, semi-sheer, and exquisitely tailored cheongsams she later wears are tools of espionage, designed to ensnare her target. For Wang Jiazhi, the cheongsam is a costume that both enables her performance and ultimately traps her within it, blurring the line between her true self and the role she must play.

| Eileen Chang’s Fictional Wardrobes | |

|---|---|

| Work | Symbolism of the Cheongsam |

| Lust, Caution (色,戒) | Represents transformation, deception, and weaponized femininity. The evolution of Wang Jiazhi’s cheongsams charts her journey from student to spy and her shifting identity. |

| Red Rose, White Rose (紅玫瑰與白玫瑰) | Used to contrast the two female archetypes. The “Red Rose” wears vibrant, provocative clothing, signifying passion and non-conformity, while the “White Rose” is dressed in pristine, subdued garments, reflecting her perceived purity and conventionality. |

| The Golden Cangue (金鎖記) | The protagonist Qi Qiao’s changing attire, including opulent traditional wear and later, more severe garments, reflects her psychological descent from a vibrant young woman into a bitter, miserly matriarch, her clothes mirroring the prison of her life. |

2. A Suppressed Silhouette: The Cheongsam in Revolutionary Narratives

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the cultural landscape shifted dramatically. The cheongsam, with its associations of Western influence, urban bourgeoisie, and individual sensuality, was condemned as a symbol of a decadent past. It was largely replaced by the unisex, utilitarian Zhongshan suit (Mao suit) or simple worker’s trousers and jackets. Individuality in dress was suppressed in favor of collective identity.

In literature written about or during this period, the cheongsam becomes a ghost, a symbol of a forbidden history. Its presence signifies a character’s connection to the pre-revolutionary world and often marks them as a target for political persecution. In Anchee Min’s memoir Red Azalea, which details her experience during the Cultural Revolution, the memory of beautiful, colorful clothing stands in stark contrast to the drab, shapeless uniforms of the era. The desire for such beauty is portrayed as a form of silent rebellion. The physical erasure of the cheongsam from the streets of China is mirrored by its symbolic weight in literature as a lost object of beauty and freedom, representing a world of personal expression that the revolution sought to eradicate. The garment becomes a shorthand for class status, foreign taint, and a life that was no longer permissible.

3. The Diasporic Wardrobe: Nostalgia, Identity, and Reinvention

As Chinese communities spread across the globe, the cheongsam traveled with them, but its meaning was transformed. For diasporic writers, the dress often serves as a tangible link to a forsaken or reimagined homeland. It becomes a vessel for nostalgia, a symbol of cultural heritage that immigrant parents cling to in a new and alienating world.

In Amy Tan’s seminal novel, The Joy Luck Club, the cheongsam appears as a relic from the mothers’ lives in pre-1949 China. It is a part of their stories of glamour, hardship, and loss. For their American-born daughters, the garment is often fraught with complexity. It can represent the heavy weight of cultural expectations or an exoticized version of Chinese identity they feel disconnected from. The act of trying on a mother’s old cheongsam becomes a powerful literary moment where the daughter physically attempts to inhabit her mother’s past, bridging the generational and cultural gap.

Conversely, for other characters, the cheongsam can be a source of shame, representing an otherness that prevents them from assimilating. The dress becomes a point of contention between generations, symbolizing the struggle to define a hybrid identity.

| The Cheongsam’s Meaning: A Comparative View | |

|---|---|

| Context | Primary Symbolism |

| Republican China Literature | Modernity, female emancipation, urban sophistication, sexual agency, and individuality. |

| Post-1949 Mainland Literature | Bourgeois decadence, counter-revolutionary sentiment, a forbidden past, and a dangerous link to Western or “feudal” values. Often its absence is more significant than its presence. |

| Diasporic Literature | Nostalgia for a lost homeland, cultural heritage, generational conflict, the burden of tradition, and the negotiation of a hybrid identity. It can be both a source of pride and a symbol of alienation. |

4. The Fabric of Femininity: Agency and the Gaze

The defining feature of the modern cheongsam is its celebration of the female form. This inherent sensuality makes it a complex and often contested symbol of femininity in literature. Its form-fitting nature inevitably brings questions of agency and objectification to the forefront: is the woman wearing the dress in control of her sexuality, or is she being packaged for the male gaze?

Literary narratives explore this duality with great nuance. In some stories, a character’s choice to wear a cheongsam is an act of empowerment, a reclamation of her body and allure. This is evident in Geling Yan’s The Flowers of War, where the courtesans of Nanjing, dressed in their vibrant cheongsams, use their perceived femininity and beauty as a shield and a source of defiant dignity amidst the horrors of war. Their silk dresses are a splash of life against a backdrop of death.

However, the cheongsam has also been co-opted by a Western gaze that often exoticizes and stereotypes Asian women, most famously embodied by the “Suzie Wong” archetype. Diasporic writers frequently grapple with this legacy, exploring how the cheongsam can feel like a costume that imposes a narrow, fetishized identity on them. Understanding the garment’s construction—the choice of fabric, the height of the slit, the cut of the bodice—is key to interpreting its function. Resources like the specialist website Cheongsamology.com offer deep dives into the historical and sartorial details of the dress, providing a rich context that can illuminate an author’s specific choices and deepen a reader’s appreciation of its symbolic power within a text. The difference between a modest, day-wear cotton cheongsam and a shimmering, high-slit silk brocade one can signify a world of difference in a character’s intent and circumstance.

5. Contemporary Threads: Globalization and Cultural Pride

In the 21st century, the cheongsam continues to evolve, both in reality and in literature. In contemporary China, the dress has experienced a revival, shedding its politically fraught past to become a symbol of national pride and cultural confidence, often worn at weddings and formal state functions. Contemporary Chinese literature reflects this, using the cheongsam to signify a connection to a reimagined, globalized Chinese tradition.

In recent diasporic literature, the symbolism has shifted again. In Kevin Kwan’s satirical novel Crazy Rich Asians, the cheongsam is less about nostalgia and more about status, tradition, and power within a transnational, ultra-wealthy elite. It is worn by matriarchs like Eleanor Young to assert authority and an unshakeable adherence to tradition. Here, the cheongsam is not a link to a lost past but a marker of an enduring and powerful present. Furthermore, contemporary authors explore the cheongsam through the lens of hybridity. A character might pair a vintage cheongsam top with ripped jeans, creating a visual metaphor for their own mixed identity—a fusion of East and West, tradition and rebellion. This deconstruction of the garment in literature shows that its story is far from over; it remains a dynamic symbol, continuously being re-stitched and reinterpreted by new generations of writers.

From the smoky glamour of Eileen Chang’s Shanghai to the fraught family dynamics of Amy Tan’s San Francisco, the cheongsam persists as a uniquely resonant literary symbol. It is a garment that contains multitudes. It can be a declaration of independence or a silken cage; a badge of cultural pride or a marker of painful othering; a whisper of the past or a bold statement about the future. More than just an item in a character’s wardrobe, the cheongsam is a narrative device in its own right. Its seams hold the stories of women navigating a century of profound change, its fabric imprinted with the intricate patterns of history, memory, and identity. In literature, the cheongsam is not merely worn; it speaks.