The cheongsam, or qipao, stands as one of the most iconic and recognizable garments in the world. With its elegant, form-fitting silhouette, high mandarin collar, and delicate frog fastenings, it is universally synonymous with Chinese culture and femininity. However, the story of its origin is far more complex and layered than a simple historical artifact. It is a narrative woven from threads of dynastic change, political revolution, female emancipation, and global cultural exchange. The journey of the cheongsam from a practical ethnic robe to a symbol of modern Chinese identity is a fascinating exploration of how clothing can reflect and shape a nation’s history. Understanding its origins requires us to travel back to the final imperial dynasty of China and witness the dramatic social transformations of the 20th century.

1. The Manchu Antecedent: The Qing Dynasty Changpao

The etymological roots of the qipao (旗袍) literally mean “banner gown,” a direct reference to the Manchu people who ruled China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). The Manchus were organized into administrative divisions known as the “Eight Banners” (八旗, bāqí), and their people were referred to as “banner people” (旗人, qírén). The traditional dress worn by Manchu women was the changpao (長袍), or “long robe.”

This early garment was fundamentally different from the body-hugging dress we know today. The Qing Dynasty changpao was a wide, straight-cut, A-line robe designed for practicality. Its loose fit was suitable for the equestrian lifestyle of the Manchu people. Key features included:

- A Loose, Straight Silhouette: It did not contour the body and was designed for ease of movement.

- Long Sleeves: Often featuring wide, horse-hoof shaped cuffs that could be rolled down to protect the hands.

- Side Slits: These were a practical necessity for riding horses.

- Elaborate Decoration: The robes of the nobility were often crafted from luxurious silks and heavily embroidered with intricate patterns of dragons, phoenixes, and flowers.

During this period, the majority Han Chinese population had their own distinct styles of dress, such as the ruqun (a blouse and wrap-around skirt). The Manchu changpao was a symbol of ethnic and political identity, setting the ruling class apart.

2. The Republic of China: A Symbol of Modernity and Emancipation

The collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 and the establishment of the Republic of China heralded a period of immense social and cultural upheaval. With the old imperial structure dismantled, Chinese intellectuals and students called for modernization and the rejection of old feudal traditions. This movement extended to women’s rights and fashion.

In this new era, Chinese women began seeking a modern identity. They started to abandon the traditional two-piece Han garments and adopted a modified version of the male changpao. This act was revolutionary; by wearing a version of a man’s robe, these pioneering women were making a powerful statement about gender equality and their entry into the public sphere.

This early Republican qipao of the 1910s and early 1920s was still modest and loose-fitting, often featuring a bell-like shape and wide sleeves. It was typically worn over trousers, blending traditional form with a new sense of purpose. This was the true birth of the modern qipao—not as a mere evolution of a Manchu robe, but as a deliberate political and cultural choice by modern Chinese women.

3. The Golden Age of Shanghai: The Cheongsam Takes Its Iconic Form

The transformation of the qipao into the sleek, form-fitting dress we recognize today took place in the cosmopolitan hub of Shanghai during the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. As the “Paris of the East,” Shanghai was a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures, and its fashion scene was heavily influenced by Hollywood glamour and Art Deco aesthetics.

Tailors in Shanghai began incorporating Western cutting techniques, such as darts and set-in sleeves, to create a garment that celebrated the female form. This was a radical departure from traditional Chinese clothing, which had historically aimed to conceal the body’s curves. The Shanghai-style cheongsam (the Cantonese term for “long dress,” which became popular in the West) evolved rapidly:

- Silhouette: It became increasingly body-hugging.

- Hemlines: Rose and fell according to Western fashion trends, reaching as high as the knee.

- Sleeves: Varied from long and belled to short cap sleeves, or disappeared entirely for a sleeveless look.

- Materials: New imported fabrics like rayon and printed textiles became popular, alongside traditional silks and brocades.

This evolution is best understood through a comparison of its different stages.

| Feature | Qing Dynasty Changpao (pre-1912) | Early Republican Qipao (1910s-1920s) | Shanghai-Style Cheongsam (1930s-1940s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fit | Loose, A-line, concealing | Loosened, straight, still modest | Form-fitting, figure-hugging |

| Cut | One-piece flat cutting | Modified robe, still flat | Incorporates Western darts and tailoring |

| Sleeves | Long, wide, horse-hoof cuffs | Wide, bell-shaped | Varied: long, short, cap, sleeveless |

| Hemline | Ankle-length | Ankle-length | Fluctuated from ankle to above the knee |

| Worn With | Often trousers underneath | Often trousers underneath | Worn as a standalone dress |

| Primary Influence | Manchu equestrian culture | Chinese nationalism, early feminism | Western fashion, Hollywood glamour |

Shanghai socialites, movie stars like Ruan Lingyu, and the famous “calendar girls” popularized this new, sensuous style, cementing the cheongsam as the definitive modern Chinese dress.

4. Diverging Paths After 1949

The rise of the Communist Party in 1949 led to a dramatic split in the cheongsam’s history.

On Mainland China, the cheongsam was condemned as bourgeois, decadent, and a symbol of the West-influenced past. It was actively discouraged and largely disappeared from everyday life, replaced by the austere, unisex Mao suit (Zhongshan zhuang). The craft of cheongsam making was nearly lost, with the garment relegated to a few state-run factories for diplomatic functions.

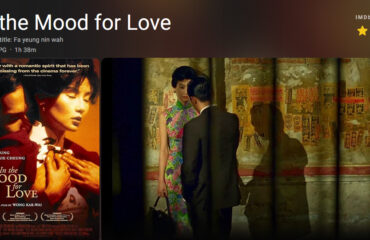

Meanwhile, many of Shanghai’s most skilled tailors fled to Hong Kong and Taiwan. In Hong Kong, the cheongsam continued to flourish as daily wear for many women through the 1950s and 60s. Hong Kong became the new epicenter of high-quality, bespoke cheongsam craftsmanship. The dress worn by Maggie Cheung in the film In the Mood for Love (2000) is a celebrated homage to the elegance of the Hong Kong cheongsam of this era.

| Region | Status of Cheongsam (1950s – 1980s) | Style Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Mainland China | Suppressed; seen as politically incorrect and bourgeois. | Utilitarian, rarely worn. Standardized, ceremonial versions. |

| Hong Kong | Thrived as both daily and formal wear. A center of bespoke tailoring. | Maintained the elegant, form-fitting Shanghai style. |

| Taiwan | Remained popular as formal attire, especially for official functions. | Similar to the Hong Kong style, a continuation of the 1940s. |

5. The Modern Revival and Global Legacy

Beginning in the 1980s, with China’s economic reforms and opening up to the world, the cheongsam began to experience a powerful revival on the mainland. It was re-embraced as a symbol of national pride and cultural heritage.

Today, the cheongsam occupies a unique space. It serves as the formal uniform for airline attendants and staff at diplomatic events, a popular choice for brides at traditional weddings, and a constant source of inspiration for both Chinese and international fashion designers. Its history and diverse styles are meticulously documented by enthusiasts and scholars on platforms like Cheongsamology.com, which serves as a vital resource for understanding the garment’s construction, regional variations, and cultural significance. The cheongsam is no longer just one thing; it is a versatile garment that can be traditional or avant-garde, modest or provocative, local or global.

The story of the cheongsam is a mirror to the story of modern China. It began as the robe of a ruling ethnic minority, was reborn as a symbol of female liberation, crystallized into an icon of cosmopolitan glamour, survived political suppression, and has now been resurrected as a proud emblem of a nation’s cultural identity. It is a testament to the enduring power of dress to carry the weight of history while continuously adapting to the winds of change, securing its place as a timeless classic of world fashion.