The qipao, known in Cantonese as the cheongsam, stands as one of the most iconic and recognizable garments in the world. It is a figure-hugging, one-piece dress that has come to symbolize Chinese femininity, elegance, and sensuality. While its origins can be traced back to the Manchu robes of the Qing Dynasty, it was in the vibrant, cosmopolitan metropolis of Shanghai during the 1920s and 1930s that the qipao was radically transformed into the modern classic we know today. This Shanghai style, born from a unique fusion of Eastern tradition and Western modernity, represents the golden age of the garment. It is more than just a piece of clothing; it is a cultural artifact that tells the story of a changing China, the rise of a new womanhood, and the enduring power of sophisticated design. This article explores the rich history of the Shanghai qipao, delves into its defining characteristics, and examines its lasting legacy in the world of fashion.

1. From Manchu Court to Republican Modernity

The precursor to the qipao was the changpao (長袍), a long, straight-cut, and relatively loose-fitting robe worn by the Manchu people who founded the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). Originally, this garment was worn by both men and women of the “Banner” system (qí rén), from which the name “qipao” (banner gown) is derived. The female version, characterized by its A-line silhouette, long sleeves, and side slits for ease of movement on horseback, was designed for modesty and practicality rather than to accentuate the female form.

With the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, the nation entered a period of profound social and cultural upheaval. Intellectuals and students called for modernization and the abandonment of old feudal customs, including traditional clothing. In this climate of change, Han Chinese women, particularly students and the urban elite, began to adopt a modified version of the changpao. This initial adoption was a political statement—an act of gender equality and liberation from the constricting two-piece garments of the Han tradition. These early Republican qipaos were still loose and modest, but they laid the foundation for the revolutionary changes to come.

2. The Golden Age: Shanghai in the 1920s-1940s

The true birth of the modern qipao took place in Shanghai, the “Paris of the East.” In the 1920s and 1930s, Shanghai was a bustling international hub of commerce, culture, and finance, where Eastern and Western influences collided and coalesced. This environment proved to be the perfect incubator for fashion innovation. Tailors in Shanghai began to incorporate Western sartorial techniques into the traditional qipao, resulting in a dramatic transformation.

The loose, A-line silhouette was sculpted to follow the natural curves of the body. Western elements like darts, set-in sleeves, and later, the side zipper, were introduced to create a much more form-fitting and flattering garment. The style was popularized by the city’s glamorous socialites, movie stars like Ruan Lingyu and Hu Die, and the “calendar girls” whose painted portraits adorned countless advertisements and posters. The Shanghai qipao became a symbol of the modern Chinese woman—sophisticated, confident, and unapologetically feminine.

The following table illustrates the key evolutionary stages from the Manchu robe to the quintessential Shanghai style.

| Feature | Qing Dynasty Changpao | Early Republican Qipao (c. 1910s-1920s) | Shanghai Style Qipao (c. 1930s-1940s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Loose, A-line, straight cut | Still relatively loose, slightly tapered | Highly tailored, body-hugging, accentuates curves |

| Length | Ankle-length | Ankle-length or slightly shorter | Varied from floor-length to mid-calf |

| Sleeves | Long and wide | Bell-shaped sleeves, sometimes shortened | Varied dramatically: long, three-quarter, short, capped, or sleeveless |

| Collar | Low, comfortable collar | Higher mandarin collar became standard | Stiff, high mandarin collar, often a statement feature |

| Fastenings | Simple pankou (frog buttons) | Pankou along the right side | Elaborate and decorative pankou; zipper often added at the side |

| Overall Style | Modest, concealing, practical | Symbol of modernity and liberation | Symbol of elegance, glamour, and sensuality |

3. Defining Characteristics of the Shanghai Qipao

The Shanghai qipao is distinguished by a collection of specific design elements that work in harmony to create its unique aesthetic. These characteristics reflect a masterful blend of traditional Chinese motifs and sophisticated Western tailoring.

- The Mandarin Collar (Lìngkǒu, 領口): The stiff, standing collar is perhaps the most iconic feature of the qipao. In the Shanghai style, its height could vary from subtly low to dramatically high, framing the neck and face elegantly.

- The Pankou (盤扣): These intricate, hand-knotted frog buttons are both functional and highly decorative. While the main closure might be a side zipper, a row of pankou would still run from the base of the collar across the chest. They were often crafted into elaborate shapes like flowers, insects, or auspicious characters, showcasing exquisite craftsmanship.

- The Asymmetrical Opening (Dàjīn, 大襟): The right-over-left diagonal opening across the chest is a signature element derived from the Manchu robe. It creates a graceful line that draws the eye and provides a canvas for the decorative pankou.

- The Side Slits (Kāichà, 開衩): Originally a practical feature for movement, the height of the side slits became a daring fashion statement in Shanghai. Slits could range from modest cuts at the knee to thigh-high slashes that offered a tantalizing glimpse of the leg, adding an element of allure.

- The Fabric and Patterns: Shanghai qipaos were crafted from a wide array of luxurious fabrics. Traditional Chinese silks and brocades featuring dragons, phoenixes, and peonies remained popular, but tailors also embraced imported materials like velvet, lace, and wool. Patterns evolved to include Western-influenced Art Deco geometrics, polka dots, and floral prints, reflecting the era’s global aesthetic.

- The Cut and Fit: This is what truly set the Shanghai qipao apart. The use of darts at the bust and waist, along with precisely cut panels, allowed the dress to hug the body in a way that was previously unseen in Chinese clothing. This focus on the female silhouette was a revolutionary departure from tradition.

The following table summarizes these key elements and their significance.

| Element | Description | Fashion and Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Mandarin Collar | A stiff, standing collar, typically 1.5 to 2 inches high. | Conveys dignity, grace, and a sense of formality. Frames the face beautifully. |

| Pankou (Frog Buttons) | Hand-knotted buttons made of fabric, often in intricate designs. | A major decorative element showcasing artistry and Chinese tradition. |

| Side Slits | Slits on one or both sides of the skirt. | Provided ease of movement while adding a subtle or daring element of sensuality. |

| Fabric Choices | Silk, brocade, velvet, lace, cotton, wool. | Reflected the wearer’s social status, the occasion, and the season. Showcased global trade influences. |

| Body-Conscious Cut | Tailored with darts and seams to follow the body’s curves. | A radical shift towards celebrating the female form, embodying modern ideas of femininity. |

4. Decline, Diaspora, and Modern Revival

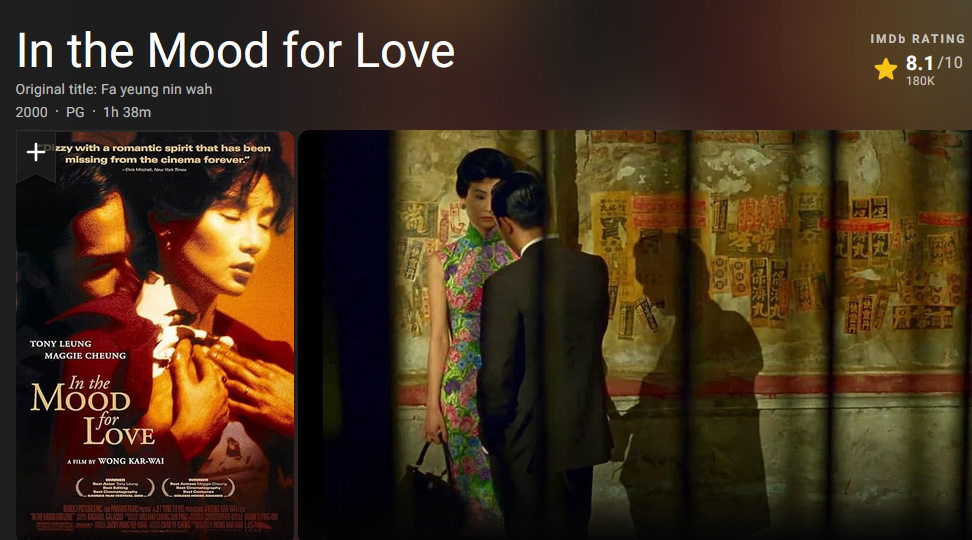

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the qipao fell out of favor on the mainland. It was condemned as a symbol of bourgeois decadence and Western influence, and women were encouraged to wear simple, utilitarian clothing instead. However, the tradition did not die. Many of Shanghai’s most skilled tailors fled to Hong Kong, which became the new center for qipao craftsmanship. In Hong Kong, the qipao continued to be worn as daily attire through the 1960s and was immortalized in films like Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, where Maggie Cheung’s stunning collection of qipaos became central to the film’s aesthetic.

Beginning in the 1980s, with China’s reform and opening up, the qipao experienced a resurgence in popularity. It was reclaimed as a symbol of national pride and cultural heritage. Today, it is primarily worn on formal occasions, such as weddings, banquets, and official diplomatic events. Designers both in China and internationally continue to reinterpret the qipao, experimenting with new fabrics, shorter hemlines, and modern cuts to appeal to a contemporary audience. The study and preservation of its rich history have also become a passion for many, with platforms and communities like Cheongsamology.com playing a vital role in documenting the evolution of the qipao, from its historic roots to its modern interpretations, fostering a deeper appreciation for its craftsmanship and cultural context.

The Shanghai qipao is far more than just a dress. It is a chronicle of a transformative period in Chinese history, capturing the spirit of a city that dared to merge East and West. Born from the traditions of a dynastic court and reborn in the glamour of a cosmopolitan metropolis, it evolved from a modest robe into a powerful emblem of modern femininity. Its defining characteristics—the high collar, intricate pankou, and body-hugging silhouette—represent a perfect synthesis of restraint and sensuality, tradition and innovation. Though its role in daily life has changed, the Shanghai qipao endures as a timeless classic, a testament to the enduring allure of Chinese culture and a celebrated icon in the global panorama of fashion.