To the uninitiated eye, the traditional garments of East Asia can appear as a beautiful but homogenous tapestry of silk, intricate patterns, and elegant silhouettes. The flowing robes of China and the iconic T-shaped garments of Japan, in particular, are often confused, their shared historical threads weaving a narrative of cultural exchange that can obscure their distinct identities. However, beneath the surface of these aesthetic similarities lies a rich history of divergence, innovation, and unique cultural expression. While Japanese traditional wear owes a significant debt to its Chinese predecessor, it evolved along a unique path, resulting in clothing that is fundamentally different in form, function, and philosophy. Delving into the nuances of Chinese Hanfu, the modern Cheongsam, and the Japanese Kimono reveals a fascinating story of how two cultures, while geographically close, crafted their own unique visual languages through fabric and thread.

1. The Ancient Roots: Chinese Hanfu and the Origins of East Asian Attire

The term “Hanfu” (汉服) literally translates to “Han clothing” and refers to the diverse systems of traditional dress worn by the Han Chinese people for thousands of years, prior to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). It is not a single garment but a vast and varied wardrobe that evolved across different dynasties, each with its own distinct aesthetic. The fundamental components of most Hanfu styles, however, remained consistent.

The most common form consists of an upper garment, the yi (衣), and a lower garment, the chang (裳). The yi is typically a cross-collared robe, wrapped with the right side over the left (yōulǐng zuǒrèn), a crucial detail as the opposite was considered barbarian or reserved for burial attire. The sleeves were often long and exceptionally wide, flowing freely with the wearer’s movements. The chang was a skirt, worn by both men and women in ancient times. Another key style is the shenyi (深衣), a long one-piece robe created by sewing the yi and chang together.

Hanfu is characterized by its flowing lines, layered construction, and an emphasis on natural, graceful movement. The silhouette is generally A-line or H-line, designed to drape loosely over the body rather than constrict it. Belts or sashes, known as dai (带), were used to secure the robes but were often slender and less of a visual focal point compared to the garment itself. The fabrics—luxurious silks, brocades, and fine ramie—were canvases for exquisite embroidery depicting dragons, phoenixes, flowers, and landscapes, each carrying deep symbolic meaning. Today, Hanfu is experiencing a powerful revival movement (hanfu yundong), as young people in China and across the diaspora embrace it as a way to connect with their ancestral heritage.

2. The Japanese Evolution: The Kimono’s Journey

The Kimono (着物), meaning “thing to wear,” is the quintessential traditional garment of Japan. Its origins can be traced directly to Hanfu, introduced to Japan via cultural exchanges primarily during China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), a period of immense cultural influence. Early Japanese court wear closely mirrored Tang-style Hanfu. However, over centuries, the Japanese began to adapt and refine these designs, leading to the creation of the Kimono as we know it today.

This evolution involved simplification. While Hanfu has countless variations in cut and construction, the Kimono developed into a more standardized T-shaped, straight-lined robe. This form, perfected during the Edo period (1603-1868), was easier to construct and fold. Unlike the often multi-piece Hanfu, the Kimono is a single robe wrapped around the body, always with the left side over the right.

The most defining feature of the Kimono is the obi (帯), a wide, often stiff and ornate sash tied at the back. The obi is not merely functional; it is a central decorative element and its intricate knot, the musubi, can signify the wearer’s status and the formality of the occasion. The Kimono silhouette is distinctly columnar, intentionally concealing the body’s curves to create a smooth, cylindrical shape. This flat surface is considered the ideal canvas for showcasing the beautiful textiles. The sleeves, while wide, are sewn shut along much of their outer edge, creating a large, pocket-like pouch. The length of the sleeve drop, known as the furi, is significant; for instance, the furisode (“swinging sleeves”) kimono with its very long sleeves is worn exclusively by unmarried young women.

3. A Tale of Silhouettes, Sashes, and Sleeves: Key Differentiators

While both traditions share the cross-collar design, the specific visual elements provide clear points of distinction. The differences in silhouette, fastening, and sleeves are the most immediate giveaways.

| Feature | Chinese Hanfu | Japanese Kimono |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Flowing, A-line or H-line, layered, emphasizes graceful movement and draping. | Columnar, T-shaped, restrictive, creates a smooth, cylindrical surface. |

| Construction | Diverse; commonly a two-piece set of a top (yi) and skirt (chang), or a one-piece robe (shenyi). | A single T-shaped robe wrapped around the body. |

| Sash/Belt | Typically a narrow sash or belt (dai), often tied simply in the front or at the side, and sometimes hidden by outer layers. | A very wide, stiff sash (obi) that is a major decorative focal point, tied in a complex knot (musubi) at the back. |

| Sleeves | Extremely wide and open at the cuff, creating a bell-like, flowing effect. | Wide but sewn partially closed to create a large pocket-like pouch. The length of the sleeve drop indicates age and marital status. |

| Collar | Cross-collar (yōulǐng zuǒrèn), generally softer and fits closer to the neck. | Cross-collar (left-over-right), wider, stiffer, and often pulled back to expose the nape of the neck (emon), which is considered alluring. |

| Footwear | Various styles of cloth shoes, often with upturned toes or decorative embroidery. | Worn with traditional split-toe socks (tabi) and sandals (zori or geta). |

4. Modern Interpretations: The Cheongsam (Qipao)

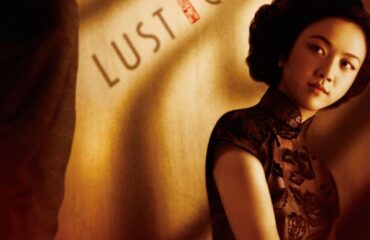

A common point of confusion is the Cheongsam (known as Qipao 旗袍 in Mandarin), often presented internationally as “traditional Chinese dress.” In reality, the Cheongsam is a relatively modern garment with a separate lineage from Hanfu. It emerged in Shanghai in the 1920s, a product of a unique cultural moment.

The Cheongsam was an adaptation of the changpao, the straight, loose-fitting robe worn by Manchu women during the Qing Dynasty. In the cosmopolitan and modernizing environment of Republican China, tailors began to incorporate Western cutting and tailoring techniques, resulting in a form-fitting, body-hugging silhouette that was a radical departure from the body-concealing robes of the past. Its key features—the high mandarin collar, the frog-style fastenings (pankou), the side slits, and the figure-accentuating cut—are iconic.

Unlike Hanfu and the Kimono, which hide the body’s form, the Cheongsam was designed to celebrate it, symbolizing the modern Chinese woman who was breaking free from feudal constraints. It is a powerful symbol of modern Chinese femininity, but it should not be mistaken for the ancient clothing of the Han people. Contemporary designers and platforms like Cheongsamology.com showcase how the Cheongsam continues to evolve, blending tradition with modern fashion sensibilities.

5. Cultural Context and Occasions for Wear

The role these garments play in contemporary society also highlights their differences. The Kimono, while not daily wear, has retained a continuous and well-defined role in Japanese life. It is worn for significant life events and ceremonies, such as weddings, tea ceremonies, funerals, and Coming of Age Day (Seijin no Hi). The lighter cotton yukata is still commonly worn for summer festivals.

The use of Hanfu is different. After being suppressed and replaced during the Qing Dynasty, its use was discontinued for over 300 years. The current Hanfu movement is a conscious effort to reclaim a lost piece of cultural identity. Therefore, Hanfu is worn today mostly by enthusiasts for cultural festivals, historical events, themed gatherings, and artistic photoshoots.

The Cheongsam occupies a space between the two. It is widely recognized as a formal dress and is often worn at weddings, parties, and formal functions. It also serves as a stylish uniform in high-end hospitality sectors and remains a popular choice for festive occasions like Chinese New Year.

Though born from a shared heritage, the traditional clothing of China and Japan tells two distinct stories. Hanfu is a diverse and ancient system, a testament to thousands of years of dynastic history, characterized by its flowing, ethereal grace. The Kimono is its descendant, a uniquely Japanese innovation that traded flowing lines for a structured, columnar elegance, creating a formal wear steeped in ritual and aesthetic minimalism. The modern Cheongsam stands apart, a symbol not of ancient tradition but of cultural fusion and 20th-century modernity. To appreciate these garments is to look beyond the silk and embroidery and see the history, philosophy, and identity woven into every seam. They are living pieces of culture, each beautiful, each significant, and each with its own proud story to tell.