The cheongsam, or qipao, is far more than a mere garment. It is a silhouette woven into the very fabric of modern Chinese history, a potent symbol of femininity, national identity, and the complex interplay between tradition and modernity. Originating in the tumultuous early 20th century, its evolution from a loose-fitting robe to the iconic, form-hugging dress mirrors the profound social and cultural shifts that defined the era. For over a century, this elegant garment has captivated the artistic imagination, serving as a powerful muse for painters and photographers who have sought to capture not just the beauty of its form, but the depth of its meaning. Through their lenses and brushstrokes, the cheongsam is transformed from an article of clothing into a narrative device, a canvas upon which the stories of Chinese womanhood and cultural identity are painted. This article explores the cheongsam’s enduring journey through modern Chinese art, tracing its depiction from the vibrant commercialism of Republican Shanghai to the nostalgic and conceptual interpretations of the contemporary art world.

1. The Modern Woman Personified: Republican Era Glamour (1920s-1940s)

The Republican era was a period of radical change. The fall of the last imperial dynasty and the influence of the May Fourth Movement unleashed new ideas about science, democracy, and individual freedom. For women, this meant unprecedented opportunities for education, employment, and social participation. The cheongsam became the uniform of this new, modern woman. Evolving from the wider Manchu gown, it was streamlined and tailored, eventually becoming the famously sleek and sensuous dress of 1930s Shanghai.

Art of this period, particularly commercial art, seized upon the cheongsam as the ultimate symbol of modernity and allure. The most prominent examples are the “calendar posters” (月份牌, yuèfèn pái), which advertised everything from cigarettes to cosmetics. These posters featured beautifully rendered “calendar girls” who embodied a new urban ideal. Clad in fashionable, often brightly patterned cheongsams, they were depicted engaging in modern leisure activities: playing tennis, driving automobiles, or enjoying a gramophone. Artists like Zheng Mantuo and Xie Zhiguang perfected a style that blended Western realism with Chinese aesthetic sensibilities, creating idealized portraits of confident, stylish women who were both quintessentially Chinese and globally modern.

In the realm of fine art, painters trained in Western academic styles also turned their attention to the cheongsam. Artists like Pan Yuliang, one of China’s most important modern female artists, painted self-portraits and figure studies that featured the cheongsam. Unlike the commercial perfection of the calendar posters, these works were often more personal and introspective, using the garment to explore themes of identity and self-representation within a rapidly changing society.

| Feature | Calendar Posters (月份牌) | Fine Art Painting |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Commercial Advertisement | Artistic Expression & Exploration |

| Depiction of Woman | Idealized, glamorous, aspirational “modern girl” | Personal, introspective, often complex and psychological |

| Artistic Style | Polished, vibrant, decorative, designed for mass appeal | Varied; often blended Western academic techniques with personal style |

| Contextual Setting | Modern, urban, leisure-focused (e.g., cafes, cars) | Often intimate or studio settings, focused on the individual |

| Symbolism | Progress, consumerism, modern lifestyle | Personal identity, cultural negotiation, the artist’s gaze |

2. A Suppressed Symbol: The Cheongsam in Hibernation (1949-1980s)

With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the cultural landscape shifted dramatically. The cheongsam, with its associations of urban bourgeoisie, Western influence, and individual sensuality, was deemed a relic of a decadent, pre-revolutionary past. It disappeared from public life on the mainland, replaced by the practical and unisex lánbù shān (blue worker’s jacket) and the “Mao suit.”

Consequently, the cheongsam vanished from mainland Chinese art. The dominant artistic style of the era was Socialist Realism, which mandated that art serve the revolution. Paintings and sculptures depicted heroic workers, stalwart peasants, and dedicated soldiers. Women were portrayed as strong and capable contributors to the socialist cause, their individuality subsumed by their collective role. In this ideological climate, there was no place for the elegance and individualism represented by the cheongsam.

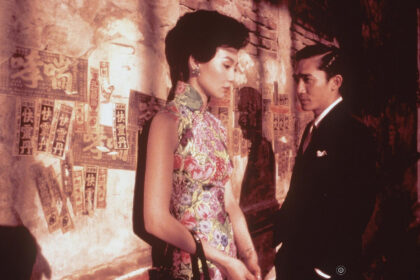

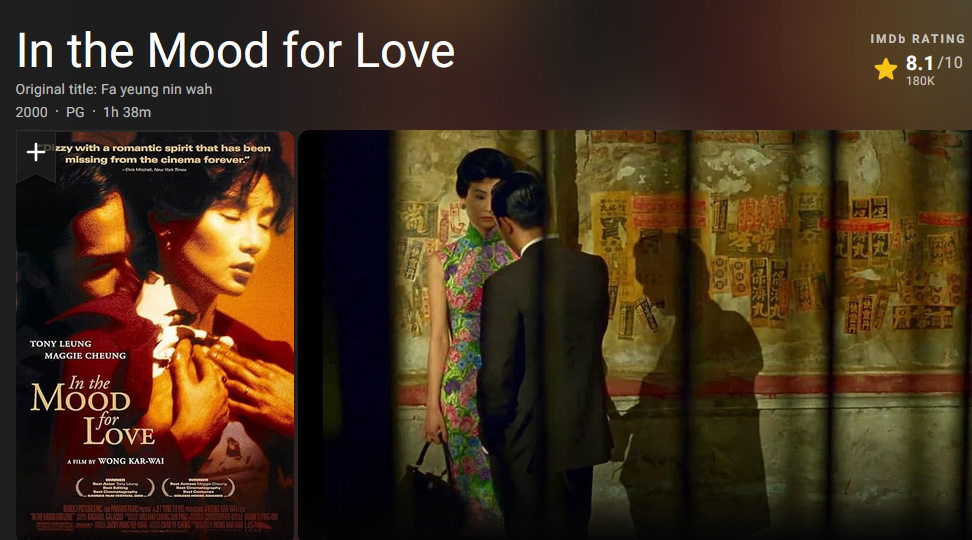

However, while suppressed on the mainland, the garment continued to thrive in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and diasporic communities worldwide. It became a powerful symbol of cultural continuity, a link to a Chinese identity separate from the mainland’s political narrative. This is most vividly seen in the Hong Kong cinema of the 1950s and 60s, where actresses like Li Lihua and Linda Lin Dai graced the screen in exquisite cheongsams, solidifying the garment’s association with timeless elegance. The iconic film In the Mood for Love (2000) by Wong Kar-wai, while made later, is a masterful artistic ode to this period, using Maggie Cheung’s stunning array of cheongsams to convey emotion, constraint, and unspoken desire.

3. The Return of the Muse: Nostalgia and Contemporary Reinterpretation (1990s-Present)

Following the Reform and Opening-Up policies of the late 1970s, China began to slowly rediscover its pre-revolutionary past. By the 1990s, this blossomed into a full-fledged cultural phenomenon, with a powerful wave of nostalgia for the perceived glamour and sophistication of Republican-era Shanghai. The cheongsam was central to this revival.

No artist is more associated with this nostalgic return than Chen Yifei. His wildly popular series of paintings, often referred to as his “Shanghai Dream” or “Old Shanghai” series, feature melancholic, beautiful women in opulent interiors, draped in luxurious cheongsams. Rendered in a highly realistic, cinematic style, Chen Yifei’s women are not the confident “modern girls” of the calendar posters. Instead, they appear wistful and contemplative, their gazes distant. They embody a romanticized memory, a beautiful but lost world. His work captured the national mood of looking back to forge a new identity, and in doing so, he cemented the image of the cheongsam as the ultimate symbol of this romantic nostalgia.

Contemporary photographers have also embraced the cheongsam, but often with a more critical or conceptual eye. Fine art photographers use the garment to explore complex themes of gender, identity, and the weight of history. The cheongsam can be used to question the male gaze, to deconstruct stereotypes of Chinese femininity, or to highlight the tension between the modern Chinese woman and the historical expectations embodied by the dress. In fashion photography, the cheongsam is constantly being reinvented—paired with leather jackets, deconstructed into new forms, or used in avant-garde shoots that challenge its traditional connotations.

| Era | Dominant Theme | Key Mediums | Representative Artists / Styles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican Era (1920s-40s) | Modernity & Allure | Calendar Posters, Oil Painting | Zheng Mantuo, Pan Yuliang |

| Mao Era (1949-80s) | (Absence) Revolution & Collectivism | Socialist Realist Painting, Propaganda Posters | (No cheongsam depictions) |

| Contemporary (1990s-Present) | Nostalgia, Identity, Critique | Oil Painting, Fine Art & Fashion Photography | Chen Yifei, Wong Kar-wai (Film), various contemporary photographers |

4. The Fabric of Concept: The Cheongsam in the Digital Age

In the 21st century, artists have moved beyond simply representing the cheongsam to deconstructing and conceptualizing it. The garment itself, or its patterns and motifs, can become the medium. Installation artists might use hundreds of cheongsams to create powerful statements about mass production, memory, or the female experience. Conceptual artists might photograph a worn, tattered cheongsam to speak of the passage of time and the fragility of cultural identity.

The digital realm has opened new frontiers for the cheongsam’s artistic life. In digital illustration and animation, it is often used as visual shorthand for “Chinese elegance.” Moreover, online communities and specialized platforms have become virtual galleries and archives. Websites like Cheongsamology.com play a crucial role in this ecosystem, not only by offering modern interpretations of the garment for sale but also by documenting its history and celebrating its depiction in art and film. These platforms foster a global community of enthusiasts and scholars, ensuring that the dialogue around the cheongsam is vibrant, informed, and accessible to a new generation. They create a space where the historical muse and the contemporary creation can coexist and be appreciated in tandem. Through these digital avenues, the cheongsam continues its journey as a subject of artistic inquiry and cultural celebration.

The cheongsam’s journey through modern Chinese art is a reflection of China’s own turbulent and transformative century. It has been a symbol of bold modernity, a forbidden relic of a “feudal” past, a vessel for romantic nostalgia, and a complex signifier of contemporary identity. From the commercial posters of Shanghai’s golden age to the melancholic canvases of contemporary painters and the conceptual explorations of today’s multimedia artists, the cheongsam has proven to be an inexhaustible muse. It is a garment that contains multitudes, at once embodying personal style, collective memory, and national narrative. As artists continue to grapple with the meaning of Chinese identity in a globalized world, they will undoubtedly continue to turn to the elegant, evocative silhouette of the cheongsam, ensuring its story is constantly retold and reimagined for generations to come.