When one thinks of iconic traditional Chinese clothing, the image that most often springs to mind is the Cheongsam, or Qipao. This elegant, form-fitting dress has become a global symbol of feminine grace and Eastern beauty, celebrated on red carpets and in cinematic masterpieces. Yet, in the rich tapestry of Chinese sartorial history, the Cheongsam has an equally distinguished and historically significant male counterpart: the Changshan. Often overlooked in the global fashion consciousness, the Changshan is a garment of profound cultural weight, embodying a unique blend of scholarly refinement, stately authority, and timeless elegance. To truly appreciate the story of Chinese dress, one must look beyond the Cheongsam and explore the dignified silhouette of the long robe designed for men. This article delves into the history, construction, cultural significance, and modern relevance of the Changshan, restoring it to its rightful place in the narrative of traditional Chinese attire.

1. A Journey Through Time: The Origins and Evolution of the Changshan

The roots of the Changshan (長衫), which literally translates to “long shirt” or “long gown,” are firmly planted in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), China’s last imperial dynasty. It evolved from the changpao (長袍), the traditional robe of the Manchu people who founded the dynasty. Initially, the changpao was a practical garment for the equestrian Manchu horsemen, its loose fit and side slits allowing for freedom of movement. When the Manchus came to power, the changpao was established as part of the official dress code for men, worn by officials, nobles, and scholars of the court.

With the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, the Changshan underwent a transformation. It shed some of its imperial formality and was adopted by the new intellectual and political elite as a symbol of modern Chinese identity—a bridge between ancient tradition and a new era. It became the favored attire of scholars, educators, merchants, and gentlemen, projecting an aura of quiet dignity and intellectualism. After 1949, the Changshan’s prevalence declined sharply in mainland China in favor of the more austere Mao suit. However, it continued to be worn with pride in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and among overseas Chinese communities, where it remains an important garment for formal occasions and cultural celebrations.

| Era | Key Developments of the Changshan |

|---|---|

| Early Qing Dynasty (c. 1644–1800) | The Manchu changpao is established as official attire. Characterized by a loose fit, horseshoe cuffs, and practicality for an equestrian lifestyle. |

| Late Qing Dynasty (c. 1800–1912) | The garment becomes more standardized and tailored, losing some of its nomadic features and becoming a symbol of status for the scholar-gentry class. |

| Republic of China (1912–1949) | The Changshan is embraced as a national garment. It becomes more streamlined and is often paired with a Western-style fedora or leather shoes, symbolizing a blend of Chinese tradition and modernity. |

| Post-1949 | Use declines in Mainland China but is preserved in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and diasporic communities as formal and ceremonial wear. |

| Contemporary Era | Experiencing a revival as heritage wear, with modern designers reinterpreting its classic form for a new generation. |

2. Deconstructing the Garment: Key Features and Design Elements

The elegance of the Changshan lies in its understated yet precise construction. Each element serves both a functional and aesthetic purpose, contributing to its distinguished profile. Unlike the body-hugging Cheongsam, the Changshan is defined by its straight, dignified lines.

Key features include:

- Mandarin Collar (立領, lìlǐng): A straight, stand-up collar that encircles the neck without folding over. It lends the garment a formal, stately appearance.

- Pankou (盤扣, pánkòu): These intricate, hand-tied knotted buttons, often made from the same fabric as the gown, run from the collarbone diagonally across the chest and down the side. They are a decorative hallmark of traditional Chinese tailoring.

- Straight, A-line Cut: The Changshan is cut straight from the shoulders, falling loosely over the body to the ankles. This A-line silhouette provides comfort and a dignified drape.

- Side Slits: High slits on one or both sides are essential for ease of movement, a practical feature retained from its equestrian origins.

- Fabrics: Traditionally crafted from materials like silk, brocade, and fine cotton for formal wear, and linen or ramie for everyday use. Modern versions experiment with a wider range of textiles, including wool blends and synthetics.

While distinct, the Changshan and Cheongsam share a common design language, as both evolved from Manchu clothing. Enthusiasts and researchers, such as those contributing to platforms like Cheongsamology.com, meticulously document the lineage and design principles that connect these male and female garments.

| Feature | Changshan (for Men) | Cheongsam (for Women) |

|---|---|---|

| Silhouette | Straight, A-line, loose-fitting. | Form-fitting, sheath-like, accentuates body curves. |

| Length | Typically ankle-length. | Varies from short to ankle-length. |

| Collar | Mandarin collar. | Mandarin collar. |

| Fastenings | Pankou (frog buttons) on a diagonal placket. | Pankou (frog buttons) on a diagonal placket. |

| Sleeves | Long and straight. | Can be sleeveless, cap-sleeved, or long-sleeved. |

| Side Slits | High slits for movement. | Often features high slits for allure and movement. |

| Primary Expression | Dignity, scholarship, formality. | Elegance, sensuality, grace. |

3. The Changshan and its Variations: More Than Just a Long Robe

The term “Changshan” is often used as a general descriptor, but the world of traditional Chinese male attire includes several distinct garments that are frequently worn in combination with it. Understanding these variations reveals a more nuanced picture of its use.

- Changpao (長袍): Often used interchangeably with Changshan, changpao is the more historically formal term for the long robe. Today, the distinction is largely semantic, though some may use changpao to refer to more ornate, ceremonial versions.

- Magua (馬褂): This is a waist-length or hip-length jacket with a central front opening, designed to be worn over the Changshan. Its name translates to “riding jacket,” revealing its origins as outerwear for Manchu horsemen. The combination of a Changshan and a Magua was once considered the pinnacle of formal attire for men, akin to a modern three-piece suit.

- Tangzhuang (唐裝): Often mistakenly called a Changshan, the Tangzhuang is a different garment altogether. It is a jacket—not a robe—that combines the Mandarin collar and frog buttons with a more Western-style tailoring structure. The modern Tangzhuang was popularized as a festive jacket during the 2001 APEC summit in Shanghai and is not a direct historical garment in the same way the Changshan is.

| Garment | Type | Primary Characteristics | How It’s Worn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changshan/Changpao | Long Robe | Ankle-length, side opening with Pankou, side slits. | Worn as a standalone formal garment. |

| Magua | Jacket | Waist or hip-length, central front opening. | Worn as an outer layer over a Changshan for added formality or warmth. |

| Tangzhuang | Jacket | Mandarin collar, Pankou, but with a modern jacket cut. | Worn as a standalone jacket, often for festive occasions. Not a robe. |

4. Symbolism and Cultural Significance

Beyond its physical form, the Changshan is imbued with deep cultural symbolism. Historically, it was the attire of the literati, the educated class who were the custodians of Chinese culture and philosophy. To wear a Changshan was to project an image of refinement, knowledge, and moral integrity. It was deliberately designed to conceal the form and de-emphasize the physical, instead drawing attention to the wearer’s dignified bearing and intellectual presence.

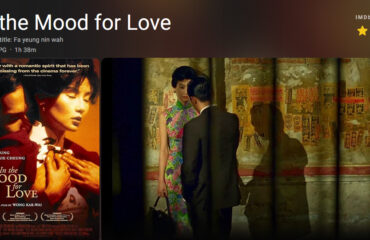

This association has been powerfully reinforced in popular culture. In cinema, the Changshan is the quintessential uniform of kung fu masters, most famously in the “Ip Man” film series, where Donnie Yen’s character wears it with an air of stoic discipline and quiet strength. In historical dramas and films by directors like Wong Kar-wai, the Changshan evokes a nostalgic sense of a bygone era of elegance and tradition.

Today, its primary role is ceremonial. It is a popular choice for grooms at traditional weddings, worn by elders during Chinese New Year festivities, and donned for other significant cultural rites of passage. In these contexts, the Changshan acts as a powerful link to ancestral heritage, a visible expression of cultural identity and respect for tradition.

5. The Changshan in the Modern Wardrobe

Can a garment with such a long history find a place in the 21st-century wardrobe? While the Changshan is not a staple of daily wear, it is experiencing a quiet renaissance. A new generation of designers in China and beyond is re-examining its classic form, experimenting with modern fabrics, shorter hemlines, and simplified tailoring to make it more accessible.

For the modern man, incorporating the Changshan can be a sophisticated style choice. For a formal event like a wedding or gala, a well-tailored silk or linen Changshan is a unique and elegant alternative to the Western tuxedo. Modern interpretations, sometimes shortened to three-quarter length and made from fabrics like denim or wool, can be worn as a statement coat. Even elements of the Changshan, like the Mandarin collar or frog fastenings, are increasingly appearing on contemporary shirts and jackets, showcasing its enduring influence. Its revival is part of a broader movement towards embracing cultural heritage in fashion, celebrating identity through clothing that tells a story.

In a world dominated by fast fashion and Western sartorial norms, the Changshan stands as a testament to the enduring power of traditional craftsmanship and cultural identity. It is far more than just the male version of the Cheongsam; it is a symbol of a different kind of masculinity—one based not on overt display but on quiet confidence, intellectual depth, and dignified grace. As interest in cultural heritage continues to grow, the long, elegant lines of the Changshan are poised to be appreciated by a new global audience, finally stepping out from the shadow of its more famous female counterpart to claim its own spotlight.